The steep drive up P.J. McArdle Roadway takes drivers from the Liberty Bridge to the top of Mt. Washington's scenic overlook. It reveals a stunning view of Pittsburgh’s skyline and three rivers, from the Point State Park Fountain to the Birmingham Bridge.

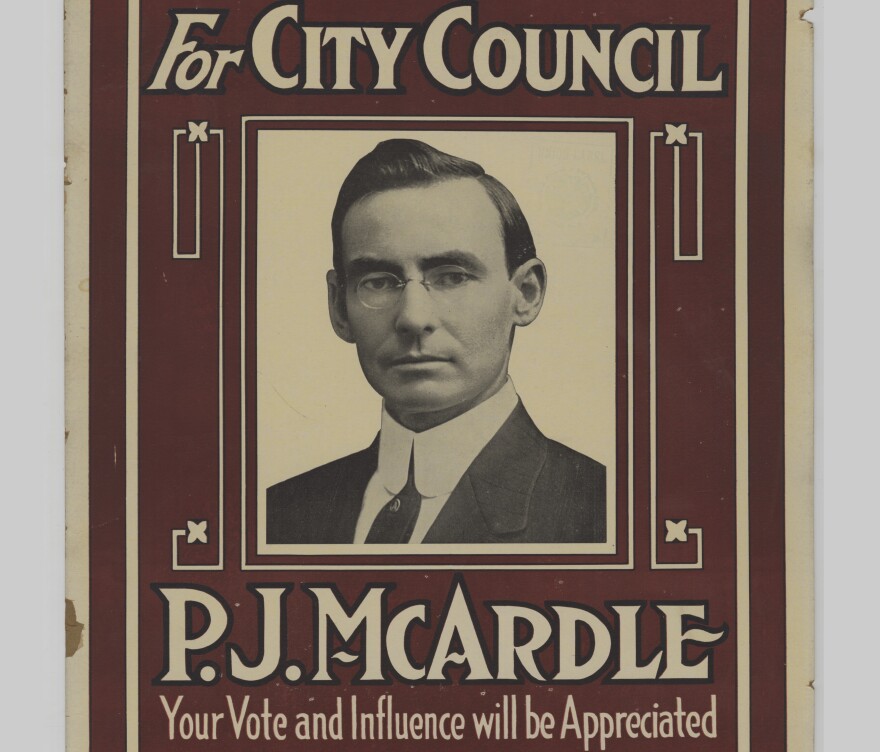

A longtime Pittsburgh city councilman, Peter J. McArdle is known for promoting development in the South Hills during his time in office, but his name is perhaps most closely associated with the road that can gets motorists there.

McArdle was born in Belpre, Ohio in 1874, moved to Muncie, Ind. and relocated to Pittsburgh when he became president of the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers in 1905.

He was a heat roller in the iron industry at a time when it was difficult to be a labor leader, said Heinz History Center historian Anne Madarasz.

“His union is in decline throughout the time that he’s involved with it,” Madarasz said. “There are changes in the industry where steel is becoming more mechanized and skilled workers, which is who this union primarily presented, are kind of being pushed off the factory floor.”

This is part of our Good Question! series where we investigate what you've always wondered about Pittsburgh, its people and its culture.

McArdle arrived shortly after the Homestead Steel Strike of 1892, when the Carnegie Steel Company locked out AA union workers, a huge setback for the labor organization.

“It loses power,” Madarasz said. “It doesn’t have the kind of authority that it had in the 1870s and 80s.”

John Lepley, a historian with the United Steelworkers, said McArdle’s years of leadership also coincided with a shift to new political strategies.

“McArdle was Irish-Catholic and a fairly conservative labor leader,” Lepley said.

During the 1910 American Federation of Labor Conference, McArdle helped form the Militia of Christ for Social Service, a small group of labor leaders dedicated to stopping the “more radical and militant” influences happening in unions at the time, according to Lepley.

But eventually McArdle left the unions behind and focused on civic leadership, serving on Pittsburgh City Council for nearly three decades, beginning in 1911. He also ran for mayor in 1933.

“This is a time in Pittsburgh where there’s a lot of progressive city planning going on,” Madarasz said, “and he’s a part of that."

Pittsburgh’s southern neighborhoods were growing thanks to annexations of Birmingham, Mt. Washington and Beechview, which created demand for transportation to get to and from Downtown. The existing inclines on Mt. Washington couldn't handle the growing population.

“This is the era of growing suburbanization, so new access routes in and out of the city were needed. The roadway completely served that purpose,” said Lepley.

A Mt. Washington resident himself, McArdle suggested building a road from the outbound side of the new Liberty Tunnel to the top of the 600-foot summit.

Workers ran into some challenges constructing the new roadway due to the mountainous topography and coal mines that were still open along the hillside at the time. Plus, they had to maneuver around the inclines, including the Castle Shannon funicular, which no longer exists.

The route ended up costing about $1 million, more than double what city planners had expected. But in 1938, the Mt. Washington Roadway was dedicated. After McArdle’s death in 1940, the road was renamed for him.

“His interest in that neighborhood and the growth of that part of the city leads him to being memorialized with this roadway,” Madarasz said.