On a sunny Sunday afternoon, a group of a few dozen people wearing baseball caps and athletic gear carry bags of baseball bats and buckets of balls to Gardner Field in Pittsburgh’s Troy Hill neighborhood.

The group counts off “one, two, one, two” to determine the teams for the day’s match. Several new teammates highfive and walk toward the dug-out, while others begin to talk about the line-up for the game.

The players are members of the Dock Ellis League, a multi-state collection of teams who describe themselves as an “open-format amateur baseball league” that is “co-Ed, queer and trans friendly, and anti-racist.”

“It’s mostly weirdos, nerds, oddballs, people that played sports when they were young,” said Alexis Cromer, who’s been playing in these games for about five years, “but may have quit because they got ostracized or yelled at by people who made them feel small.”

Dock Ellis, the league’s namesake, is described by baseball fans and Society for American Baseball Research member Paul Geisler as “one of the best pitchers of the 1970s.”

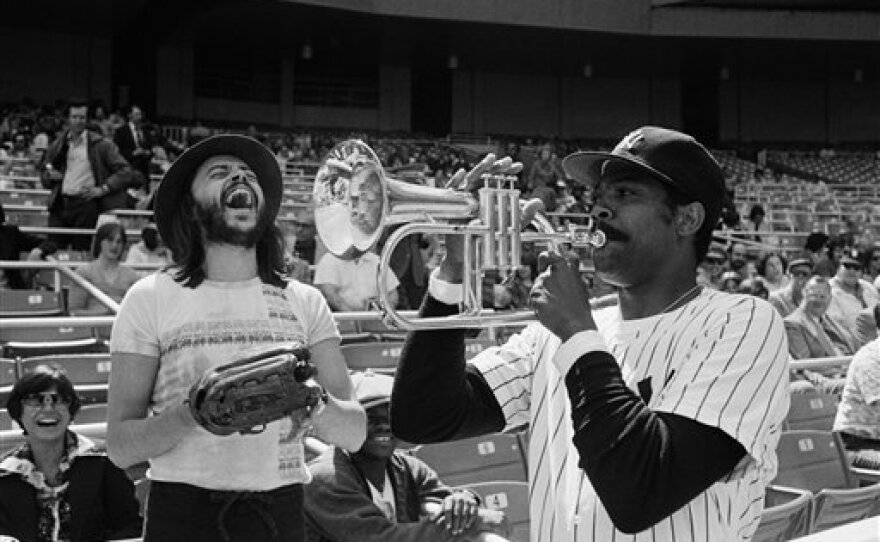

Fifty years ago this week, Ellis, who was black, pitched a no-hitter while, he says, he was high on LSD, a hallucinogenic drug also known as acid. But Geisler said his legacy extends further than that June 12, 1970 drug-powered game against the Padres in San Diego.

“He was very outspoken about racial, equal rights for players and how management was treating them,” Geisler said. “He had the voice to do that and always the support of his team.”

Dock’s background

Born in Los Angeles in 1945 to a working-class family, Ellis attended Gardena High School, where he played baseball and basketball. At the time, Geisler said the school was predominately white.

“That’s where Dock experienced some of his first racial interactions negatively,” Geisler said. “He got taunted in the hallways, in his classrooms, but he excelled in sports.”

In his teenage years, Ellis started experimenting with drugs and alcohol. He was arrested for stealing a car in 1964, placed on probation and ordered to pay a fine.

Chet Brewer, a well-known Negro League pitcher-turned-scout for the Pittsburgh Pirates, recruited Ellis. Brewer, according to a 2005 Houston Press article about Ellis (he pitched for the Rangers later in his career), encouraged the young player to sign a one-year minor-league contract with the Pirates. After four years, he made his major league debut on June 18, 1968, as a relief pitcher.

Throughout his early years playing for the team, racial discrimination was routine--such as having to stay at separate hotels from white players and sitting in different sections of the ballpark.

To help cope with the pressures of being a professional black baseball player, Geisler said Ellis continued to use drugs and alcohol.

“He still said he did not pitch a game all the way through the major leagues without using drugs or alcohol or both,” Geisler said.

Sponsored by the Baum Boulevard Automotive, Eisler Landscapes, and the CPA firm Sisterson and Company.

Still, Ellis found success in the major leagues, often maintaining a win-loss record with the Pirates. Off the field, he was a vocal advocate for black players, acting as a player representative.

Jackie Robinson, best known for breaking the color barrier in professional baseball, once wrote to Ellis.

“He got a letter from [him] hat said, ‘keep doing what you're doing.’ You're helping a lot of ballplayers,” Geisler said.

The letter reportedly also read: “There will be times when you will ask yourself is it worth it all? I can only say, Dock, it is, and even though you will want to yield in the long run, your own feeling about yourself will be most important.”

The "no-no"

Ellis had gone to stay with a friend in Los Angeles the day before a four-game series against the Padres in 1970. As the story goes, according to Ellis, he took LSD on a Thursday and Friday, either thinking he wasn’t scheduled to pitch until the next day, or not realizing what day it was.

“The girlfriend of the guy he was staying with said, ‘Hey Dock, you’re pitching today,’” Geisler said. “He said, ‘No, on Friday.’ And she said, ‘Today is Friday.’”

Ellis caught a flight from LA to San Diego and made it to the game just in time.

A 2014 film by Jeff Radice called “No No: A Dockumentary,” follows the story of that day.

“It was easier to pitch with LSD,” Ellis tells the camera. “That’s the way I was dealing with the fear of failure.”

During the game, Ellis said he also took “bennies,” Benzedrine, another stimulant. He said he didn’t see the hitters, but the catcher had put reflective tape on his fingers to make the pitching signals more visible.

“He said sometimes the ball felt like a big balloon or beach ball being thrown and other times felt like a little dart or a golf ball,” Geisler said. “And he thought he could see a comet tail flying off the ball.”

Ellis describes the batters themselves as sometimes looking like Richard Nixon or Jimi Hendrix. One rookie player, Dave Cash, called out to Ellis, telling him he had a “no-no,” or consistent innings without a hit.

“There’s a special mystique among ballplayers, one of the old traditions is a superstition that you don’t talk about it,” Geisler said.

Ellis’ no-no was a little messy: he walked eight batters and hit some, too. But nonetheless, it was a no-hitter. The Pirates won 2-0.

Dock’s later life and career

On Sept. 1, 1971, Ellis was part of the first all-black and Latino lineup, alongside beloved Pirates players Roberto Clemente and Willie Stargell. Ellis pitched against the Philadelphia Phillies.

The lineup reflected what many baseball historians call Major Leagues Baseball’s “most diverse” team at the time. The Pirates would go on to win the World Series against the Baltimore Orioles that year.

Ellis was later traded to the New York Yankees, Oakland Athletics, Texas Rangers, New York Mets and eventually returned to Pittsburgh in 1979, where he finished his career with a lifetime win-loss record of 138-119.

During his career, he also spoke out about Sickle Cell Anemia, having been diagnosed with a trait of the blood disorder as a teenager. The disease, which disproportionately affects black communities, can cause severe pain. He detailed his experience to a U.S. Senate committee and advocated for the need to find a cure as part of his membership with the Black Athletes’ Foundation.

In the next year, 1980, he entered a drug treatment facility and would go on to become a counselor for incarcerated people and other athletes struggling with addiction.

“He would say, ‘I want to go where they’re at,’” Geisler said. “You can meet them in the clubhouses and the bars.”

He became an advocate for sobriety, helping to raise money for organizations dedicated to such work. He also established the Dock Ellis Foundation, a group that helps victims of domestic violence.

Dock’s legacy

Dock Ellis died Dec. 19, 2008 in Los Angeles, but his influence in pop culture and athletics continues.

In 2011, Garfield resident Sean Lehr-Nuth was talking with some friends about forming a baseball league that would be inclusive and include “men and women, people of all different backgrounds, having a great time, competing, but putting joy above winning.”

In collaboration with some friends in New York, he formed the Dock Ellis League, starting with two teams: the Pittsburgh Pounders and Brooklyn Bruisers.

The league focused less on the competition of the game and more on the comradery.

“Many of my current teammates have a story of when they stopped enjoying sports as children, often it was an aggressive coach, parent, or teammate,” Lehr-Nuth said. “Sports became work and stopped being joyful, so we quit.”

The inclusive nature of the league is what drew Dan Nowhere to the group.

“I liked baseball a whole bunch as a kid,” Nowhere said. “Played in the little league, got the s*** kicked out of me by my teammates for being queer, quit playing sports.”

In the Dock Ellis League, Nowhere said he’s accepted for who he is, not bullied for his sexuality.

Justine Hackimer and her husband Kurt both play on Pittsburgh Dock Ellis teams and say the positivity makes games fun.

“Everybody cheers for everybody and is rooting me on,” Justine said, noting that before coronavirus she traveled a lot and was unable to attend games, but has recently started going to pick-up matches.

Games include food, music and beer; families are encouraged to bring dogs and kids to share in the fun. Now, there are seven teams in the country: Pittsburgh Pounders, Allegheny A's, West Philly Waste, Richmond Scrappers, Baltimore Hellbirds, Port City Pickles (Wilmington, NC), and the Kansas City Quitters. The teams travel to play each other throughout the season (although probably not this year, Lehr-Nuth notes, due to coronavirus) and meet people throughout the country who share their desire for inclusive baseball.

Ellis’ legacy is remembered well by players. He was “an unapologetic black man in a time when that was not the norm,” Lehr-Nuth said. And he used his platform to call out injustice and push for equality in sports and American society generally.

“Hopefully Dock would approve.”