Four bronze panther monuments keep watch over the Panther Hollow Bridge in Oakland. Weathered over a century, the statutes appear to stalk passersby.

Good Question! asker Diane Litman of Squirrel noticed the big cats and wondered about the history of panthers in the region.

“I’m interested in learning when they became extinct, what caused it,” Litman asked. Penn Hills’ Jan Hardy “wondered when the last time was that anyone saw a panther in the area.”

It’s been more than 100 years since the large felines prowled around Southwestern Pennsylvania. According to Suzanne McLaren, collection manager for the Section of Mammals at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, panthers roamed from Alaska to Panama.

“When the settlers came to North America, it was actually the most widespread mammal species on the whole continent,” McLaren said. They were already roaming western Pennsylvania when Europeans arrived in the early 1700s and could adapt to many different habitats from dense forests to grasslands. Panthers would wander more than 50 square miles to look for food, are mostly nocturnal and great climbers.

“A lot of times they’ll be hanging up in a tree on a very substantial branch and you could be hiking around and not even realize that you’re being watched,” McLaren said.

But panthers weren’t interested in eating humans. Rather, they’d prey on squirrels, deer and, back before they were driven out of the region, elk and moose. Panthers go by a few names (including cougars, pumas and mountain lions), and were solitary creatures, except during the mating season.

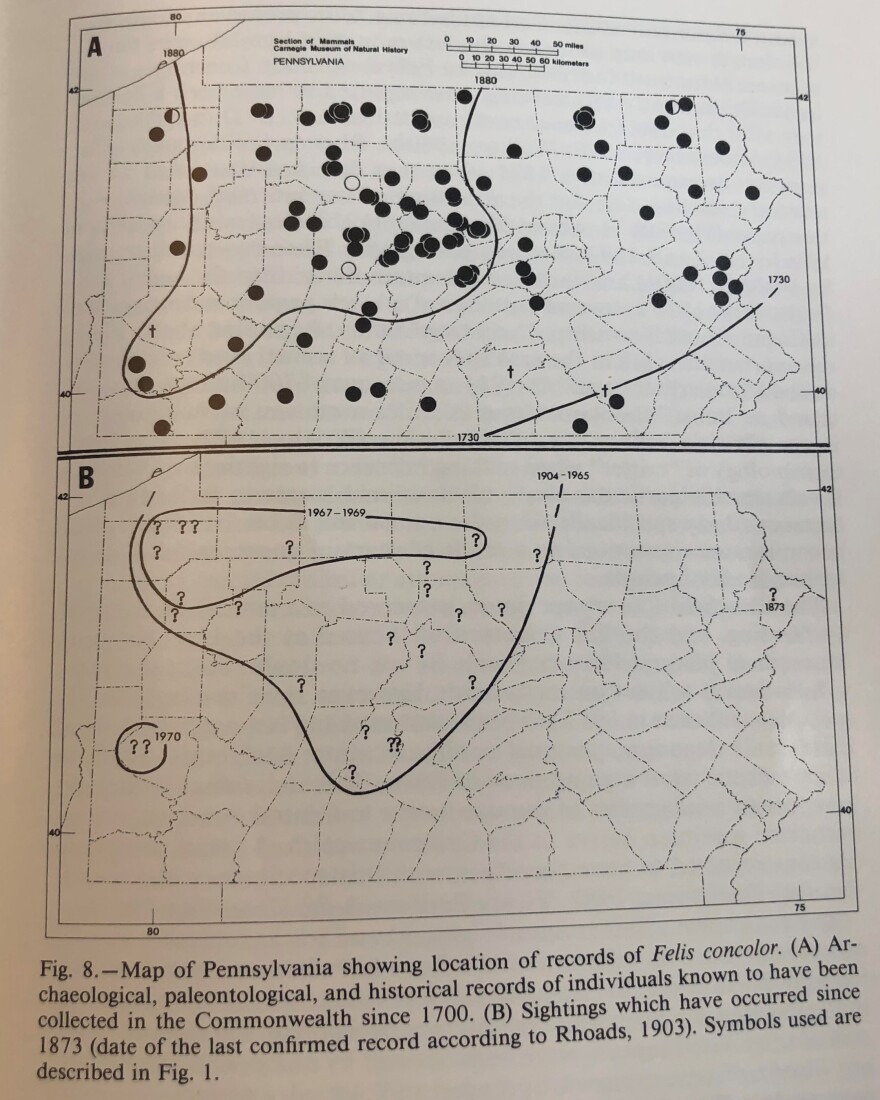

As Pennsylvania’s human population increased throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the panther population began to decline. McLaren said farmers were worried about them eating livestock, and according to a 1985 Carnegie Museum of Natural History research report, the mountain lion was feared by many residents.

“Newspaper accounts fueled these fears by attributing attacks on man and domestic animals to this species. Thus, the killing of a mountain lion was a matter of pride that was remembered by many hunters for years after a small record had been placed in the local newspaper,” the report stated.

McLaren said the decline in the species is also linked to a fluctuating deer population and logging in the state’s forests.

“The viable populations in Pennsylvania … the males and females who could find each other, for the breeding populations, were probably gone by the late 1800s,” McLaren said.

Most records of mountain lions were in the center of the state, according to the 1985 research report, likely because Allegheny County was more developed than other regions. From 1970-71, there were four sightings in Sewickley Heights.

Pitt adopts the panther

In Oakland, a different type of panther can be found: the mascot of the University of Pittsburgh. Pitt athletics historian Sam Sciullo said the animal was chosen in 1909 by alumna George M. P. Baird, who suggested the panther because it was indigenous to the area, but also because it was a “noble” animal.

“And the alliteration to it, too,” Sciullo said. “Also at that time, no other college or university used panthers as its mascot.”

Plus the golden panther fur is close to the university’s gold and blue. Athletic teams quickly latched onto the panther, with a student dressing up as one for games. ROC, as the mascot is known, was a nod to former Pitt football player Steve “the Rock” Petro. On football programs, the panther transformed from cartoonish and jolly to aggressively bearing its teeth. Sciullo said in the 1960s the panther made its way into sports rallying cries.

“They would play the growling panther at the outset of radio broadcasts or the coach’s show.”

Sponsored by the Baum Boulevard Automotive, Eisler Landscapes, and the CPA firm Sisterson and Company.

In 1967, Sciullo said the Beaver County Pitt Club purchased a baby panther and brought it to the sideline during games. It was kept at the then-Highland Park Zoo, where it lived out its life.

Artistic renditions of the animal can be seen throughout Pittsburgh from the fountainheads at the Cathedral of Learning to the cartoonish panther at the Schenley Plaza carousel. But it’s unlikely the living version will return to the region anytime soon.