Pittsburgh is familiar with deadly labor struggles, most prominently the Battle of Homestead in 1892, which pitted striking mill workers against security forces hired by industrialist Henry Clay Frick — an armed conflict on the banks of the Monongahela River. But though it’s less well-remembered, another key episode in Appalachian labor history three decades later took place some 250 miles southwest of here.

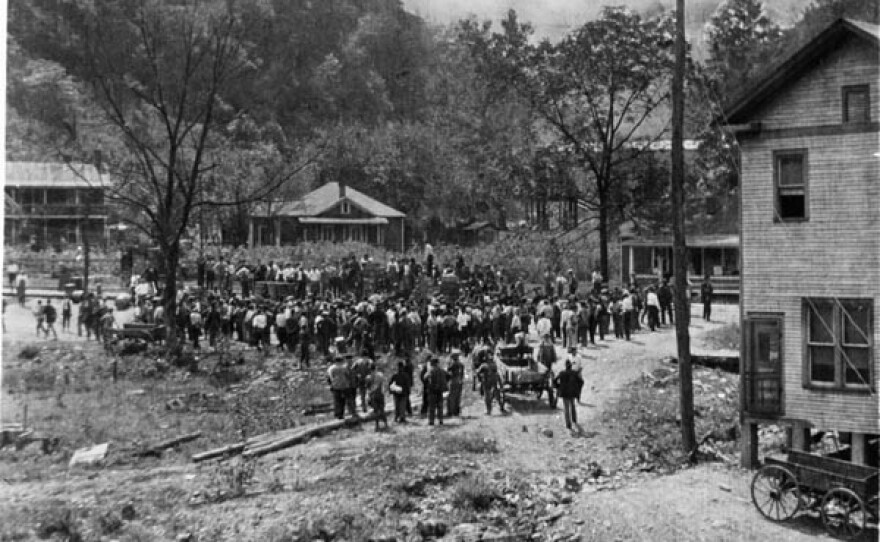

This month marks the centennial of the Battle of Blair Mountain, in which 10,000 or more armed, pro-union miners confronted some 3,000 state police, strikebreakers and private security forces hired by coal companies in Logan County, in southern West Virginia. The five-day conflict in 1921, which ended only with the arrival of federal troops, was the largest uprising on U.S. soil since the Civil War and the culmination of the West Virginia mine wars.

Chuck Keeney, a history professor and author of “Road to Blair Mountain: Saving a Mine Wars Battlefield From King Coal,” has a personal connection to that era: His great-grandfather Frank Keeney was a United Mine Workers of America district leader who was among the hundreds of people tried for treason in the wake of the mine wars. Keeney said the Battle of Blair Mountain ultimately played a role in changes to federal labor law that helped unions grow.

“It’s in some ways the fear of more violent outbreaks, particularly during the Great Depression, that in some ways helped lead to many of these reforms,” he said.

Keeney is among the experts participating in “Battle of Blair Mountain 1921: What It Means for Working People in 2021,” an online panel discussion set for Thursday, Aug. 19. The free event is sponsored by Pittsburgh’s Battle of Homestead Foundation.

The story of Blair Mountain and its legacy is complicated. Until the mine wars began, in 1912, coal miners in West Virginia were almost completely non-union, said Keeney. Within nine years, organizing efforts had unionized miners in most of West Virginia, save for three counties in the far south of the state: Logan, Mingo and McDowell.

Keeney, who teaches at Southern West Virginia Community and Technical College, said the mine wars were about more than union rights. The coal companies essentially owned the towns in what Kenney called “an industrial police state.” Along with the right to organize and bargain collectively, miners lacked basic freedom of speech — their mail was opened, for instance — and they were paid in company scrip rather than U.S. currency, curbing their economic options.

“Their rights were fundamentally being denied them,” said Keeney.

The Battle of Blair Mountain occurred after union leadership organized a 60-mile armed march from Marmet, W.Va., to Mingo to free striking miners and their families who’d been arrested after the governor declared martial law. (Another precipitating factor was the Aug. 1 murder, by gunmen from the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency, of Sid Hatfield, the pro-union sheriff of the town of Matewan and the hero of “Matewan,” the 1987 John Sayles movie dramatizing the mine wars.)

Keeney said the number of marchers might have approached 15,000. But they never made it to Mingo. In Logan County, anti-union sheriff Don Chafin and a makeshift army including state police (whom Kenney said had been formed in 1920 expressly to break strikes) confronted the marchers along a 12-mile series of ridges including Blair Mountain. It remains the largest pitched battle in the history of the U.S. labor movement.

Coal company forces had machine guns, said Keeney; the miners did not. After federal troops joined Chafin’s forces on the fifth day, the miners laid down their arms. Keeney said there were officially 20 fatalities, but that the real number was likely higher because both sides kept their casualties secret.

While the Battle of Blair Mountain made international headlines, the short-term effect on the labor movement was negative, said Keeney. “[M]ostly, the way the miners were portrayed in the media was that the reason they were revolting was because they were the product of a backward, isolated, uncivilized culture,” he said in a phone interview.

The union miners, who wore red bandannas around necks, were called “rednecks” — not the lone usage of this term at the time, but one that Keeney said helped it to earn national prominence as largely derogatory slang.

Moreover, the union movement was decimated in West Virginia. UMWA membership dropped from 50,000 members to fewer than 1,000, and deaths rose dramatically in the new nonunion mines, said Keeney.

It wasn’t until the 1930s, and the passage of federal legislation protecting unions and union organizing, that the labor movement began to gain ground again.

After years of decline, however, union membership as a percentage of the labor force today is at its lowest point in decades. Keeney said there are many echoes of that era in today’s political landscape.

“In 1921, you had a lot of racial tensions,” said Keeney. He cites the Tulsa Massacre, in which white mobs killed hundreds of Black residents of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and torched a Black-owned business district there in May 1921. “You had a resurgent KKK. Resurgent xenophobia. There were anti-immigrant laws that were being pushed … So immigration was one of the major issues.”

“The Battle of Blair Mountain itself was when the Black miners, immigrant miners and poor white miners worked together in a common cause. Those groups are often pitted against one another, particularly poor rural whites versus immigrants and Blacks,” he said. “And Blair Mountain serves as an example of the possibilities of what can happen if those groups work together as opposed to being pitted against one another.”

Besides Kenney, the Aug. 19 panel discussion includes three other representatives of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum, in Matewan: board member Catherine Moore, a professor at West Virginia Wesleyan College and editor of NPR program “Inside Appalachia”; artist and author Shaun Slifer, the museum’s artistic director and display designer; and board member Barbara Ellen Smith, an expert on black lung and former director of Women’s and Gender Studies at Virginia Tech.

The moderator is Phil Smith, director of communications and government affairs for the UMWA.

The program runs from 7:30-9 p.m. More information is here.

Details on the Battle of Blair Mountain’s official centennial celebration, taking place Labor Day weekend, are here. https://www.blair100.com/