A new grant program meant to make Pittsburgh more livable for artists of color named its first three recipients Monday.

The Pittsburgh Foundation’s Exposure Artist Fellowship is designed to address systemic racism in the Pittsburgh arts scene by supporting artists who are Black, indigenous, or people of color and who work “at the crossroads of arts, social inquiry and activism,” according to the foundation. Each artist receives $50,000, the opportunity for professional development, and a chance to pair with a local arts institution.

The inaugural recipients for this year-long pilot program include filmmaker Chris Ivey, who documents the impacts of gentrification on communities of color; multidisciplinary artist Shikeith, whose work explores the lives of Black queer men; and multidisciplinary artist Ana Armengod, who plans to collaborate with undocumented and formerly undocumented immigrants to tell their stories on film.

Ivey is paired with the Kelly-Strayhorn Theater, while Shikeith will work with the Carnegie Museum of Art. Armengod’s fellowship is self-curated.

“With the choice of these three excellent artists and two dynamic arts organizations, I’m confident that Exposure grants will deliver resources where they are most needed right now and benefit the entire arts community in the long term,” said Pittsburgh Foundation president Lisa Schroeder, in a statement.

“The co-fellowship relationship is meant to address the power dynamics within large institutions, including The Pittsburgh Foundation,” said Celeste Smith, the Foundation’s senior program officer for arts and culture, in a statement. “When the experiences of Black, indigenous and people of color are elevated, there is potential for white-led organizations, including philanthropy, to truly welcome, learn from and support them.”

Ivey, who moved to Pittsburgh in 1995, is best known for his documentary series “East of Liberty,” about the displacement of people of color from the rapidly gentrifying East Liberty neighborhood. (He began work on the project in 2005, well before “gentrification” was the Pittsburgh buzzword it later became.) He’s also documented similar dynamics as far afield as New Orleans and Capetown, South Africa.

One initiative of his the fellowship will support is a series of film screenings and public dialogues centered on Black women here and elsewhere. In March, Ivey is headed to Louisville, Ky., for the anniversary of the police killing of Breonna Taylor, accompanying a group of Black women from Pittsburgh to meet Black women leaders there. The following week, women from Louisville will visit the Kelly-Strayhorn for a similar event.

“For me it’s just trying to show Pittsburgh how we can do things better,” said Ivey. Of the fellowship, he said, “It’s good to have this support right now … and for me to try to leverage it and get more support to keep doing more work like this.”

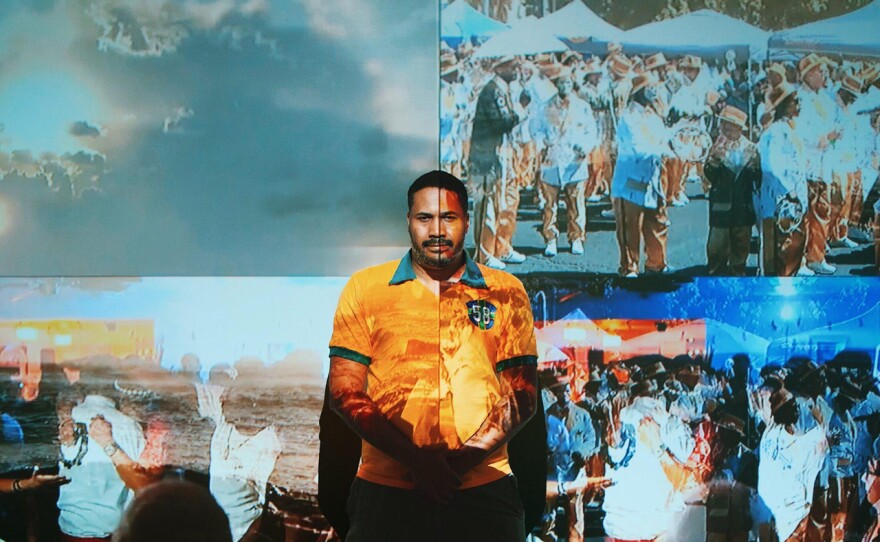

Shikeith, 32, is a Philadelphia-born artist with a growing national reputation. He’s best known for his photography and film work, though he’s also moved into sculpture and installations. Shikeith moved to Pittsburgh in 2018. Since then, he’s had a solo show at the Mattress Factory, and work in group shows around the country. In October, his work was exhibited at the Performa Biennial, in New York City, and he’s now gearing up for his first solo show in New York, which opens in May, at Yossi Milo Gallery.

He likes that the Exposure grant is unrestricted, meaning recipients can use it for any purpose. “As an artist that’s quite rare, to get funding to just kind of explore whatever ideas you may have,” he said.

Exposure artists were chosen in a multi-stage process that included anonymous nominations from the community, an application, and interviews. Applicants this round were asked to choose whether they wanted to work with the Kelly-Strayhorn or the Carnegie. Shikeith said he chose the Carnegie in part because he hadn’t worked with it before, but also because he thought the partnership could help break down some barriers between arts institutions and communities of color.

“I think as an artist who works in experimentation, what I could offer was the language of my studio,” he said. “But I think if all the artists working in this fellowship and all the people we’re working with have an open mind, I think something really amazing could come out of that.”

Armengod, 31, was born in Sinaloa, Mexico, and since her teen years has lived mostly in the U.S. She said she was formerly an undocumented immigrant herself (though a legal resident) and was in fact deported for a time, at age 26. She wants her work to illuminate the immigrant experience, which she said few non-immigrants understand.

“I think that people don’t realize that people are leaving behind these complex lives and identities and families and connections to all of their surroundings,” she said.

Unusually these days for a motion-picture artist, Armengod works primarily with Super 8 mm film, most widely known as the medium of home movies before video cameras took over, in the 1980s. She said she enjoys processing the film by hand, and that the grainy images suggest memory and nostalgia.

Her planned collaborations will be with immigrants from Mexico, other parts of Latin America, and elsewhere. She intends to use the fellowship money not only to produce the films, but also to pay her collaborators (which is not typically done in documentary work).

“I really do see my project and the way that I’m dealing with the fellowship as a vessel to help a greater community,” Armengod said.

The fellowship also includes professional development led by Felicia Savage Friedman, who will host individual and group sessions with the artists, the Carnegie, the Kelly-Strayhorn, and the Pittsburgh Foundation, to work “to examine and change systems of oppression, and encourage accountability and power sharing.”