In September 1965, a young German named Werner Herzog arrived in Pittsburgh for the first time.

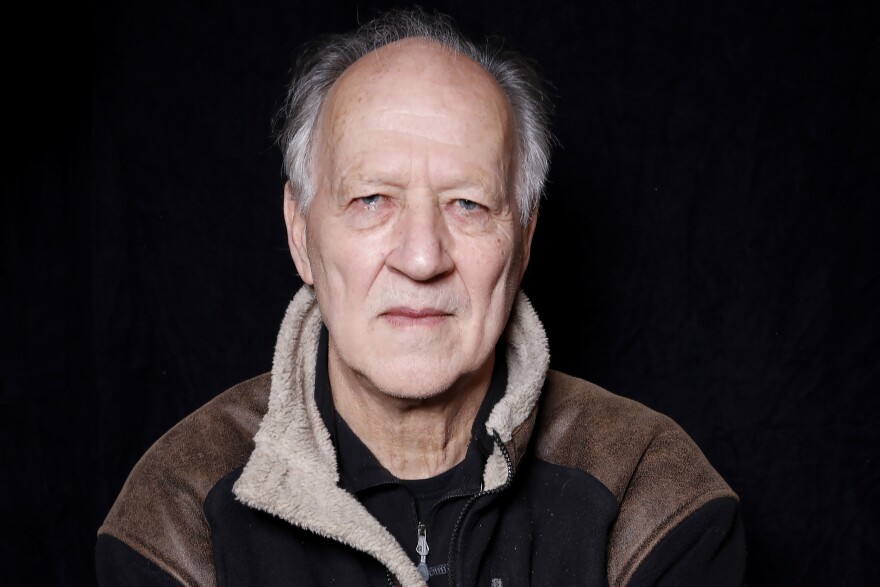

Within a decade, Herzog would be among the world’s most celebrated independent filmmakers, a prize-winner at Cannes and a leading figure in the New German Cinema. Today, he’s a cultural icon, known for his darkly existential outlook, fascination with obsessive characters — like the ill-fated protagonist of his cult-favorite documentary “Grizzly Man” — and left-field film and TV cameos.

But 58 years ago, at 23, he was a fledgling filmmaker with two shorts to his credit and a scholarship to Duquesne University.

In a new memoir out this week, Herzog writes that he chose Pittsburgh because its working-class image appealed to him, and he picked Duquesne because he’d learned it had film equipment. In “Every Man for Himself and God Against All,” however, Herzog recalls being sorely disappointed in the university. He didn’t stay enrolled long.

Yet Herzog’s memories of Pittsburgh from this time are vivid and even a bit fond — down to a long-lasting affection for the Steelers. And that was only the beginning of this internationally known artist’s oft-renewed relationship with one mid-sized American city.

The Sorrows of Young Werner

Herzog was born in Munich, in 1942. His family fled the war to Sachrang, a village in Bavaria, and, in his earliest years, Herzog was removed from popular culture. Once he discovered film, he pursued it avidly. He attended the University of Munich and then accepted the scholarship to Duquesne.

But, as he writes in his memoir (translated by Michael Hofmann), “Pittsburgh turned out to have been a bad idea.” He found Duquesne “intellectually impoverished,” he writes, its film facilities just a TV studio.

A Duquesne spokesperson said Herzog took one class that fall and audited two others; the following spring, he took just one more before leaving the school entirely. Herzog writes that he stayed part of that time with his original host, a professor who was “forty but terrified of his mother,” but recalls couch-surfing and sleeping in the library. (Herzog also remembers the local steel industry as “almost dead,” which it certainly wasn’t in the mid-’60s; he’s likely conflating this impression with memories from a visit some years later.)

In those early days, though, Herzog had at least one refuge: Duquesne magazine, the student literary publication. Constance Carroll, the senior humanities major from Baltimore who edited the magazine, recalls Herzog hanging out and sometimes taking meals at the publication's headquarters, a row house on the Bluff.

“When you met Werner, the first thing that impressed you was that he was an absolutely brilliant young man,” said Carroll in a recent phone interview. “And in addition, he had a captivating and exuberant sense of humor.”

Carroll recalls the magazine’s bohemian vibe. “We were all sort of post-beatnik, early-hippie stage,” she said. “We wore a lot of black and we knew everything, and we were dedicated to liberal and humanistic causes.”

Herzog wrote a short story for the magazine. In first-person narration, “Metamorphosis” depicts a man who, just as Herzog had, traveled to a new country by ship. The story’s character is a stowaway who has burnt his passport and is looking to start a new life. But in his shipboard hiding place he struggles to avoid “rust and filth” and adds, “There are rats here, too.” The rodent troubles escalate, finally turning surreal.

“Orphan”

Herzog’s new memoir also honors the kindly if eccentric family of Evelyn Franklin, the Fox Chapel widow who informally adopted Herzog after picking him up hitchhiking.

Herzog lived that winter with Evelyn, several of her seven children, an aged grandmother and a cocker spaniel named for Benjamin Franklin.

“I loved the Franklins,” he writes.

Evelyn called Herzog “Wiener” or “Orphan.” One of her adult sons, Billy, was “a failed rock musician” who’d run around the house naked and talk to Benjamin in “an imaginary canine language.” Once, engaging in horseplay with Evelyn’s twin daughters, Herzog leapt from a bathroom window and broke his ankle.

The Franklins, he writes, taught him “some of the best and deepest things about America.” But there was much more to his first stay in the U.S.

Herzog writes he worked “for a producer at WQED in Pittsburgh” on a documentary “about theoretical research on plasma rockets.” He names the producer as Matthias von Brauchitsch, a legendary figure at the public TV station. The film was shot largely in Cleveland, and Herzog’s detailed description suggests he spent at least a few weeks on the project. (Joe Pytka, the Braddock native and future famed director of TV commercials, told WESA via email he was the cinematographer and an editor on that film, working closely with von Brauchitsch, and has “no memory of Herzog.”)

In any case, writes Herzog, the gig ended quickly because he had no work permit. Fearing deportation, he writes, he fled to Mexico and worked for rodeos and, rather outrageously, smuggling stereos, TVs and guns; he also contracted hepatitis. Shortly, though, he returned to the U.S. and then flew to Germany.

So ended Herzog’s first visit to North America, in spring 1966, just nine eventful months after it began.

However, he still has at least one friend from that time: His Duquesne schoolmate Constance Carroll. After grad school at the University of Pittsburgh, Carroll went on to serve as president of three different community colleges in California. In addition to her two current presidential appointments — to the National Humanities Council and the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities — she heads the nonprofit California Community College Baccalaureate Association.

Carroll has followed Herzog’s career avidly and they remain in occasional contact, she said: “He’s an extraordinary person, and I have been and always will be a great fan.”

“A special attachment to this city”

Herzog had more to say to Pittsburgh.

By the time of his next visit, however, his life was very different. It was Feb. 1980, and Herzog was one of the world’s most celebrated arthouse filmmakers. With such groundbreaking peers as Volker Schlöndorff, Wim Wenders and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Herzog exemplified the New German Cinema movement that emerged in the late 1960s.

Herzog’s early films include 1972’s “Aguirre, the Wrath of God,” starring frequent (and frequently hostile) collaborator Klaus Kinski as a mad conquistador in the Amazon jungle. In 1975, Herzog won two prizes at the Cannes Film Festival, including the coveted Silver Palm, for “The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser,” a drama about a foundling with no language or knowledge of the outside world.

“He was the arthouse director at that time. He was very popular, very hot,” said Gary Kaboly, a local film aficionado and later director of exhibitions at the nonprofit Pittsburgh Filmmakers.

In January 1980, the Carnegie Museum of Art’s film and video program launched a nine-week Herzog series. Bill Judson, the museum’s curator of film and video, said in a recent interview he considered Herzog “a visual artist” whose films were like feature-length paintings, with provocative subject matter. “He sought out individuals who were separated, isolated from culture,” Judson said.

The series’ coup was booking Herzog himself for the Feb. 19 Carnegie Lecture Hall screening of “Heart of Glass,” his 1976 drama about an 18th-century village whose inhabitants are driven mad by the loss of the secret to making the ruby glass they are famous for.

All that film’s actors, famously, performed under hypnosis; they act literally while entranced. But as heard in audio archived by the museum, Herzog, now 38, was himself quite lively in his pre-show remarks and lengthy post-screening question-and-answer session.

Topics included his drawn-out ongoing project “Fitzcarraldo,” starring Kinski as an Irish would-be rubber baron whose plan to build an opera house in the Peruvian jungle somehow requires dragging a 320-ton steamship over a mountain by hand. (It’s a feat Herzog and crew replicated for the film, whose outlandish production woes were recounted in Les Blank’s classic documentary “Burden of Dreams.”)

While castigating contemporary culture for its proliferation of “worn-out” images — tourism posters, cigarette ads, television in general — Herzog even referenced his immediate environs.

“A civilization that does not have adequate language or adequate images will fade away,” he said. “We will die out like the dinosaurs in the museum next door.”

Herzog also acknowledged he’d had a tough time in his first visit to Pittsburgh, but he celebrated the presence at the screening of his foster family from Fox Chapel, the Franklins, who “literally picked me up from the streets.”

“I’m very grateful for that, and I have a very special attachment to this city, and I am very pleased that after so many years I have also found an audience for my films here,” he said.

In an interview taped the next day with the museum’s Lucy Fischer, Herzog reveals another abiding interest from his stay in the 1960s: Steelers football. He said he’s seen them play (at old Pitt Stadium) and he praised the Steelers, who just a month earlier won their fourth Super Bowl, beating the Los Angeles Rams.

“I’m very proud that the football team has won the Super Bowl. Football is a very, very fine game and they simply are the best,” he said. “They are the best … There is no doubt about it.”

“So intense”

A perhaps more memorable (if less well-documented) event took place Feb. 19, the afternoon before the evening “Heart of Glass” screening. Pittsburgh Filmmakers, a co-op that supplied photographers and filmmakers with equipment, invited Herzog to visit and sample some work by local artists.

Herzog came to the group’s second-floor walk-up on Oakland Avenue, blocks from the Carnegie. The screening room — where Filmmakers’ Brady Lewis had programmed a Herzog retrospective a few years earlier — held only about 50, and by some accounts it was full, though not everyone showed their work.

“He didn’t present himself as some sort of celebrity film director,” said Joe Seamans, a filmmaker then working at WQED. “He was just sort of like another person in the room: ‘You make films, I make films, here we are, let’s talk.’”

His wife, Elizabeth Seamans, screened a short documentary she’d made. “I remember showing him my film, and I remember him liking it a lot,” she said. “And then Tony showed ‘Sweet Sal' … and Herzog just went bananas!”

Tony Buba was then a little-known filmmaker who worked crew on George Romero films like “Dawn of the Dead” and made short, quirky documentaries about life in his hometown of Braddock. “Sweet Sal” is his spiky portrait of a verbose Braddock Street hustler who boasts of his cold-blooded deeds.

“It was like a Herzog character,” said Buba, laughing. Filmmakers had been asked to show just five minutes of their work each, but when the 16mm projector went dark on “Sweet Sal,” Buba recalls, Herzog said, “No, no, no, I want to see more, I want to see more!”

“So he watched the whole 25 minutes, and then he asked me, ‘Do you have any more films?’” he said.

Buba, mimicking Herzog’s accent, says Herzog exhorted him, “You must continue to make films, you must go steal if necessary to make films!” Buba adds, “He was just so intense!”

Buba indeed made more films; he went on to become one of Pittsburgh’s most acclaimed independent filmmakers, with screenings at festivals, film societies and museums around the world. He said his opportunities skyrocketed after Judson booked him for a November 1980 solo screening at the Carnegie, in those days a key stop on the national art-film circuit. (Buba attributes that screening to Herzog’s interest; Judson, for the record, said he would have booked the up-and-coming Buba regardless.)

“Genuinely curious”

Herzog himself only became more famous. In the 1980s, he turned increasingly to documentaries, the best-known of which remains “Grizzly Man.” He also began directing operas, a craft he’s practiced from Houston Grand Opera to the legendary La Scala, in Milan.

Herzog even returned to Pittsburgh for a couple films.

In “Jack Reacher,” a 2012 Tom Cruise thriller shot here, Herzog memorably portrays the villainous Zec, who survived a Soviet prison camp by chewing off his own fingers to escape a deadly mining detail. (It was on this trip, Herzog writes in his memoir, that he failed to locate any members of the Franklin family, with whom he had stayed in intermittent touch over the years. He writes that Evelyn, the mother, and son Billy had both died.)

A few years later, Herzog was back to interview several experts at Carnegie Mellon University for “Lo and Behold,” his essay-like documentary about robotics, artificial intelligence and the Internet.

Mike Vandeweghe, a research engineer at CMU’s National Robotics Engineering Center, remembers the experience favorably. Herzog visited NREC to learn about CHIMP, a humanoid robot that had placed third in the U.S. Department of Defense’s DARPA Robotics Challenge.

Vandeweghe said, unlike some of his colleagues, he didn’t know who Herzog was. But CHIMP had gotten a lot of media attention, and Vandeweghe was impressed that Herzog seemed to have fewer sci-fi-influenced assumptions about what the machine could do than did most journalists.

“He seemed genuinely curious about it, but he didn’t come in with his own narrative and try to make the facts fit the narrative,” Vandeweghe said.

He said Herzog was more “philosophical” than he expected, at one point asking Vandeweghe, “Does CHIMP dream?”

Starting in the mid-2000s, Herzog returned to making dramatic feature films. He’s also amassed an impressive if sometimes unlikely array of TV cameos, from “The Simpsons,” and “Parks and Recreation” to “The Mandalorian.”

Who knows if he’ll return to Pittsburgh? But even if he doesn’t, both the filmmaker and the city will always have plenty of mutual stories to tell.