Ron Madrid stood in his front yard a few blocks from downtown State College, motioning to the houses and apartments in the neighborhood, comparing the homeowners and the renters.

“When people take care of their property because they own it, that’s much different than if you’re just renting,” Madrid said. “Walk down the street, and you can say: rental, rental, somebody lives there, owner-occupied, rental.”

Over time, neighborhoods like Madrid’s have seen shifts from long-term residents to more student rentals. And a development boom currently happening in downtown State College is expected to continue that trend.

Slick, tall apartment buildings with names like “The Metropolitan” have been built or are going up around the edge of downtown.

Estimates say the building boom will increase the number of housing units in the borough by about 20 percent — largely made up of downtown rentals for students from Penn State University.

That growth troubles some residents, who worry it will change the character of the town.

Madrid, who was president of his neighborhood association for many years and ran for mayor, emphasized the pragmatic nature of the development. He served on the planning commission when State College adopted changes to its zoning that allowed for taller buildings. Now, he thinks there’s been enough of that type of development.

“It’s not as simple as people say, ‘Well, I don’t like high-rise development.’ I gotcha. Not many people do, especially here in Central Pennsylvania,” Madrid said. “But, if we wanted to redevelop downtown, that’s the price we paid.”

State College planning director Ed LeClear agrees.

He said the borough looked at where it wanted to grow. In the end, it chose higher-density development around the edge of downtown while preserving the heart of town.

He said if you don’t redevelop the town’s core so it’s an attractive, vibrant place, and bring people in, “eventually you will stagnate to the point where you don’t have enough tax revenue.”

The redevelopment includes 12-story buildings with high-end apartments for students and space for businesses and shops, largely on the lower levels.

“We’re going to see a dramatic transition over a five to six-year time frame, where we’ll have gone from being historically undersupplied to probably now having some vacancy rates and more units than we’re used to as a region,” said LeClear.

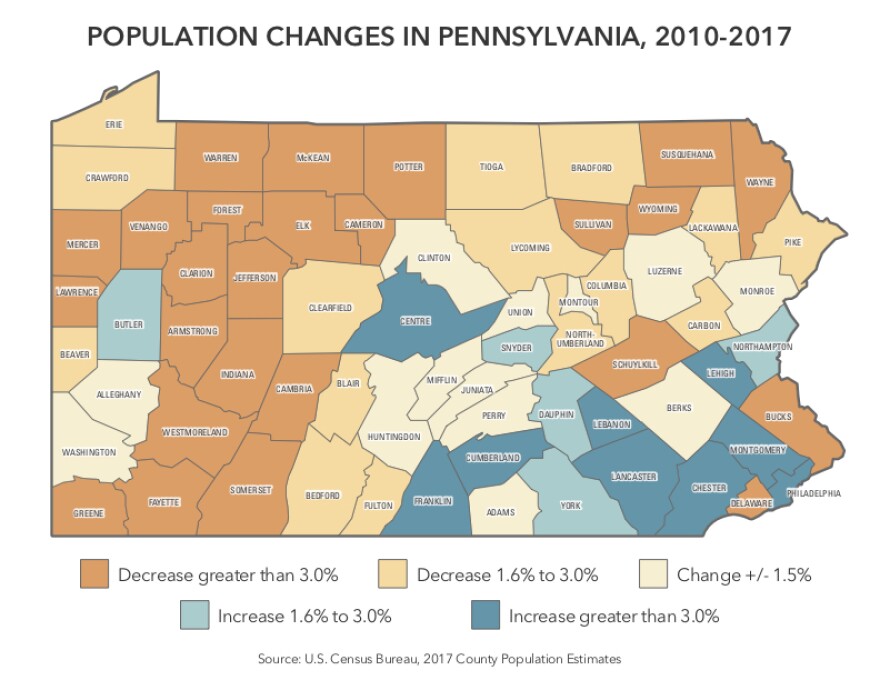

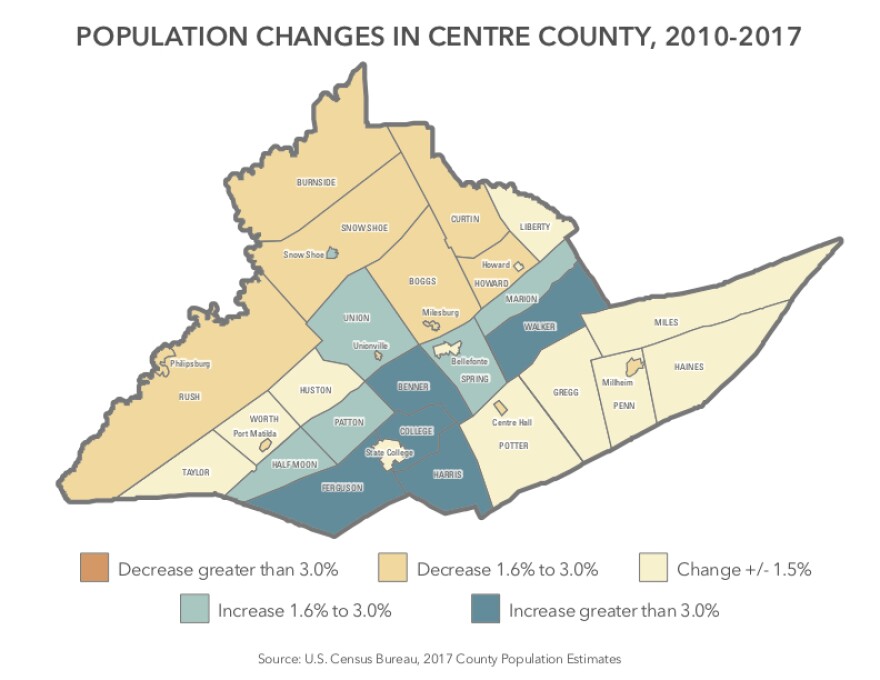

The changes are happening as Centre County has become one of the state’s hotbeds of population growth.

‘More like dorms’

Some residents think State College should focus more on making the town an affordable, desirable place for families to live.

Mark Huncik is president of a neighborhood group called the Highlands Civic Association. He said one of the reasons his family moved to State College is the walkability, including walking their daughter to school every day.

The Highlands neighborhood is next to downtown, and Huncik and others feel the effects of its growth.

“It’s not just a matter of them coming in and creating living space for the students. I think there needs to be a realization of that impact on the neighboring communities. And, we’re, as the Highlands goes, we’re right there, we’re right next to it,” Huncik said.

Susan Venegoni is vice president of the association. She says working families have a hard time affording the borough.

“I think diversity is very important,” Venegoni said. “And, if we’re constantly moving in one direction, it will be more like dorms, less like a neighborhood.”

Eric White has lived in the neighborhood since the mid-1970s. He said portraying longtime residents like they don’t want any change isn’t fair.

“All of the research I read on the sustainability of neighborhoods is about maintaining home ownership in the neighborhoods,” White said. “That the neighborhoods that are the most viable on the whole, or as the kind of neighborhoods we want, are neighborhoods where a substantial number of people who own their homes and take care of them. We have that to a certain extent here, but we’re starting to lose it.”

Penn State enrollment has been steady lately — but it’s still a major driver of these changes.

Jonathan Friedman, an attorney in downtown real estate, said after the recession, hospitality and housing grew. Interest rates dropped, more money was available and it had to go somewhere.

“Student housing became a hot commodity because of the ability to be positioned close to campuses and rent to students,” Friedman said.

At the same time, the demand for student housing outstripped the supply.

“I don’t think there’s ever plans for people to tear down all of State College and build high rises everywhere,” Friedman said. “But I think that smart, controlled growth is important.”

He says student housing can be an engine to push the community’s ideas forward. Commercial space is required on two floors of new apartment buildings in the higher-density development area. Friedman said the community can voice its opinions about what it would like to see there — certain stores, restaurants or offices.

“Utilizing that gives us an the opportunity to make the town better,” Friedman said.

Find this report and others at the site of our partner, Keystone Crossroads.