“This is not just an education law,” says U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, “this is a civil rights law.”

Duncan is referring to the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act, or ESEA, which is up for reauthorization by Congress.

“The law is outdated and fundamentally broken. We need Congress to get past this dysfunction and fix the law,” Duncan said.

President Lyndon Johnson signed ESEA as part of his war on poverty. The original intent was to ensure that federal resources would help disadvantaged and special-needs children.

Duncan said any reauthorization of the law must address equity, “making sure the children who need the most help, the children who come to school with some challenges be they English language learners or children with special needs, poor children get the help they need and deserve."

"We need to continue to focus on excellence, making sure there are high standards for every single child, making sure every single child has a chance to pursue their dreams,” he said.

In reauthorizing the law in 2002, then President George W. Bush renamed it “No Child Left Behind,” which included annual testing for students in grades 3-8 with an Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) report measuring the performance of schools.

According to Duncan, there was too much focus on a single test score.

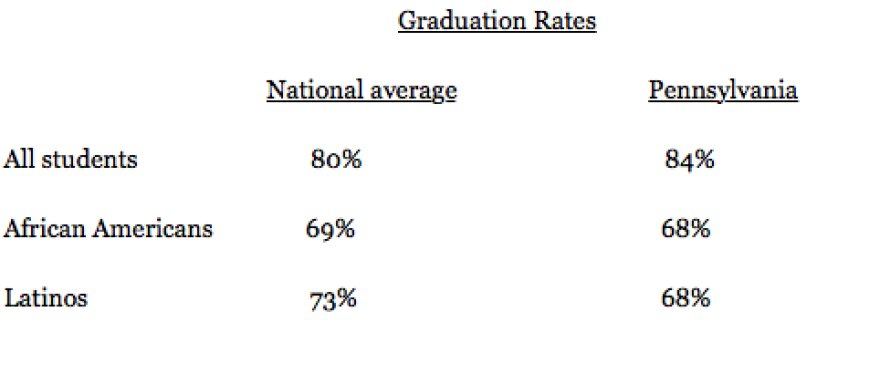

“While I believe we should assess students annually, we have to look way beyond test scores," he said. "We have to look at our graduate rates going up, our drop out rates going down, more students going on to college. The good news is graduation rates (nationally) are at all time highs, drop out rates in the black and Latino communities are down significantly.”

According to the National Center for Education Statistics* in the Department of Education, the dropout rate nationally held steady in 2012 at 3.3 percent, but in Pennsylvania, it rose to 2.8 percent from 2.2 percent the previous year.

Duncan said priorities for reforming ESEA include increasing standards, “raising the bar” for all students.

“I absolutely think the goal is to have every single child graduate from high school truly prepared for college and careers," he said. "Our simple definition there is people don’t have to take remedial classes when they get to college. The rates of remediation in higher education are staggeringly high.”

For example, he said, about one of every three high school graduates in Massachusetts who go on to public college have to take remedial classes, which means “they’re burning through Pell grants, they’re burning through our tax dollars” taking non-credit classes and have higher drop out rates.

“That’s in no one’s interests,” he said.

Duncan said equity for all students is not solely about money, but under-investing is a huge challenge.

“We’ve done an analysis in terms of spending in high poverty districts versus wealthy districts, and Pennsylvania actually has the biggest differential," he said. "There’s about a third less money being spent per pupil in Pennsylvania’s lowest poverty districts than in the wealthier districts. What that means in Pennsylvania the children who need the most are getting the least.”

Federal statistics show that in 22 other states combined spending — state and local — is less per pupil in the poorest school districts than in the most affluent districts.

Duncan said he can’t predict when or even if Congress will reauthorize and reform ESEA.

“I hope that it’s fixed," he said. "I hope it’s fixed in a bipartisan way. It’s long overdue.”

While the House is considering a Republican-supported reauthorization of the law, which the White House does not support, the Senate is working on a bipartisan version with hearings planned for April.