This is the first in a week long series exploring inequity in the Pittsburgh region.

Jonnae Carter is painting a foam stamp she made. The 3-year-old’s braids swing as she shuffles behind a table telling anyone who will listen about shapes and colors and textures.

Her mother, Raeshonda Wellen, brought her to a Buzzword event at the Homewood Early Learning Hub, a community space for caregivers. Earlier in the night, Jonnae and about two dozen kids sat rapt as a storyteller read a book about an elephant. The storyteller stopped mid-story and asked the kids if they could describe an elephant’s skin: tough, wrinkled, bumpy.

The Buzzwords program is entering it’s fourth year. It’s a project of the Cultural Trust and the Pittsburgh Association for the Education of Young Children, or PAEYC. It’s meant to introduce young children to new words, in a variety of contexts.

The word of the night was texture. After the story, the children made artwork to bring their new word to life.

Pausing during a children’s book to talk about the content is an effective way to help kids build their vocabulary, according to said Isabel Beck, a retired University of Pittsburgh professor and senior scientist.

“Just reading to the child seems to have no effect. It’s reading to the child with intermittent conversation about it,” she said.

Beck spent most of her career studying early language development. She and her colleagues at Pitt developed ways to train teachers in early grades to improve reading comprehension. Her work is often cited as a remedy to a problem first illuminated by a seminal study that came out more than 20 years ago.

Two child psychologists spent nearly three years following more than 40 families with young children. They tracked conversations between child and parent, counting how many and what types of words were exchanged. The researchers found that children in low-income families heard about 30 million fewer words than their more affluent peers by age 3. They called it an early catastrophe, and most researchers agree that gap still exists.

The 30 million word study led to more research to figure out when parents should start reading to kids. Last year, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that parents read aloud to their infants starting at birth. That was largely in response to a 2013 Stanford study suggested the word gap began as early as 18 months of age.

Beck and other researchers in her field say that gap exacerbates the way the deck is already stacked against poor kids. Children behind in kindergarten are still behind by the time they start taking standardized tests in third grade. Those children are often still behind when they graduate high school. From there, it's nearly impossible to catch up.

In Homewood, where the children gathered to listen to a story at the Buzzword event, nearly half of residents live below the federal poverty level.

While the original word gap study looked at economic status, in Pittsburgh, like in many cities, there is also a correlation to race. More than half of Pittsburgh Public School students are black and nearly half of those students are living below the poverty level.

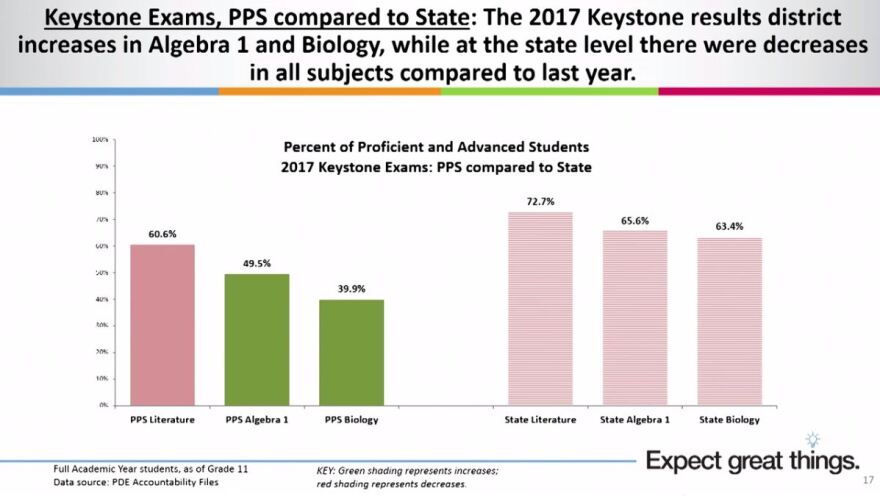

Earlier this month, Pennsylvania released last school year’s statewide standardized test results. In Pittsburgh, there was a slight overall increase in combined reading scores for 3rd through 8th grade students. When that data was presented to the school board, president Regina Holley said she was still very concerned that not all kids are improving.

“Looking at grade five for reading, the gap is 34 percent. This is unacceptable,” she said.

That means white students scored 34 percentage points higher than black students. Holley said the board is aware of the achievement gap, as well as when and how it starts. She asked that the district’s curriculum department report back how it was adapting to address the disparity.

Wellen, Jonnae’s mother, is a social worker for the Pittsburgh Public Schools system. She said she sees firsthand how the achievement gap that plagues the district starts before children even get to school. A large part of her job, she said, is finding resources for parents who are sometimes working multiple jobs and stretched for time.

“Some parents don’t understand literacy because they don’t have literacy,” she said. “So we have to work with the parents where they’re at. If they don’t know how to read, how do you expect them to help their kids with their homework?”

It’s a cycle that PAEYC is trying to break. Rachelle Duffy, director of learning and development, said supporting caregivers is essential.

“We want to make sure that those people feel comfortable and confident enough in their abilities to care for young children. It is intimidating,” she said. “It is the hardest job in the world.”

Duffy said building a child’s vocabulary isn’t always intuitive. As Beck pointed out, reading a book simply isn't enough. But by teaching caregivers how to read to children, the hope is to level the playing field so all Pittsburgh's kids have the words they need by the time they start school.

Coverage of issues of social justice and racial and economic equity in Pittsburgh on 90.5 WESA is generously supported by the Heinz Endowments.