It was a case of mistaken identity.

“I think I just saw a cat,” said Sadie Fielding, stopping near a hedge on Windsor Street in Greenfield. “I did! Hey, Penny. Except now you’re fat, why are you fat?”

“What? Why is--?” exclaimed Betsy Vicente, whipping around to investigate. “That’s Slippers!”

Vicente and Fielding attend Minadeo Elementary School in Squirrel Hill. The two friends have named all the cats along the half mile walk they make to class each morning.

Their commute is a tiny, daily adventure, said Vicente’s mom, Laura McCarthy. She thinks it plays a crucial role in her kids’ development. Vicente’s older brother also walked to school.

“It's important for kids to have some time to themselves without adult supervision,” said McCarthy. “I think they need practice making their own decisions, even if there's a chance they might make some wrong decisions. I have to trust them.”

For the 25,000 children that attend Pittsburgh Public Schools, transportation is inherently personal. Decisions made by the district about bus routes or times affect individual families, their routines and lives. But in turn, the needs of families impact how the district plans its transportation system. And it’s all very complicated.

Who can walk to school depends on distance. State law allows elementary schools to ask students to walk if they live less than a mile and a half away. For high school, the limit is 2 miles. According to Right To Know requests filled by Pittsburgh Public Schools, 5,839 of the district’s students walk. But most kids ride a bus.

The Morning Rush

At 8:12 on a recent Monday morning, Lori Bower took one last gulp of her coffee before calling upstairs to her two sons, Johnny and Artie.

“Guys, get your shoes on, we have to go!” A groan came from both boys. “Make it fast!”

Artie, 7, scooped up his bag while Bower halted Johnny, 10, just before he went out the door. He had toothpaste on his shirt, and Bower quickly wiped him down, gently rebuffing his protestations against wet shirts. It’s like this every morning, said Bower, as she ushered the boys out the door, into the car, and to their bus stop in Brighton Heights.

Bower said she wasn’t keen on her neighborhood school because she wanted a more alternative education. They applied to Pittsburgh Montessori.

“I just kept hearing that it had really involved parents and a really kind of peaceful environment,” she said. The two boys spend ninety minutes to two hours on the bus each day. Johnny isn’t the ride’s biggest fan, while Artie views it as social time, and Bower said, overall, she’s been happy with Montessori.

The Friendship school is a magnet program, so kids come from all over the district and usually have a longer ride. Parents like Bower accept that as part of the deal. But some kids spend just as much time on the bus as Johnny and Artie to get to their assigned school.

For instance, some English Language Learners travel from the North Side to Lawrenceville to go to Arsenal Elementary. Superintendent Anthony Hamlet rode with them one morning in the fall of 2016.

“It took us 50 minutes to an hour in the morning, one way,” he said. “When I did the commute, I guess the time change hadn’t happened yet, so it was dark. [When] we got on the bus, it was pitch black.”

Unlike the restrictions on walking, there is no state law that regulates how long a student can be on a bus, said Megan Patton, transportation project manager for PPS.

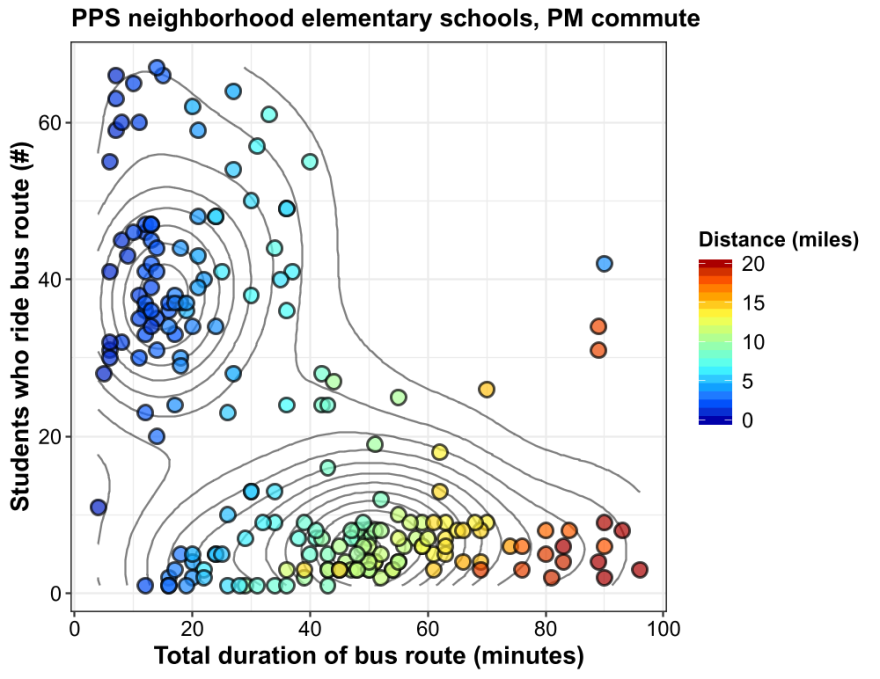

“We do try to keep students on the bus like 45 minutes at the max,” she said.

Hamlet said he would like to see trips closer to 30 minutes. But it’s a logistical puzzle, said Eldridge Black, director of pupil transportation.

“If people would be able to see the inner workings, behind the scenes, what’s all involved I think it would create a greater appreciation for what we do,” he said.

Transportation remains one of the largest line items in the district’s budget; it hit the $35 million mark in fiscal year 2018. The growth of magnet and charter schools means families have more choices. But those choices come at a cost to the district, said Black.

“Now they have more options and we have to fulfill those options,” he said. “When you go out of your feeder zone it makes our expenses go up even more.”

On top of paying for out-of-feeder schools such as magnets and charters, the district is also on the hook to transport private and parochial school students. In the 2012-2013 school year, 60 percent of the kids living in Pittsburgh went to a school other than their neighborhood school. The district doesn’t have more current numbers, but officials expect a study wrapping up this month to give them a better snapshot.

If more families choose schools outside their neighborhood, the transportation puzzle will continue to grow more complicated and more expensive.

In the final part of our "Dividing Lines" series, Sarah Schneider looks at how Pittsburgh Public Schools plans to keep students in the district. Find more at wesa.fm/dividinglines.