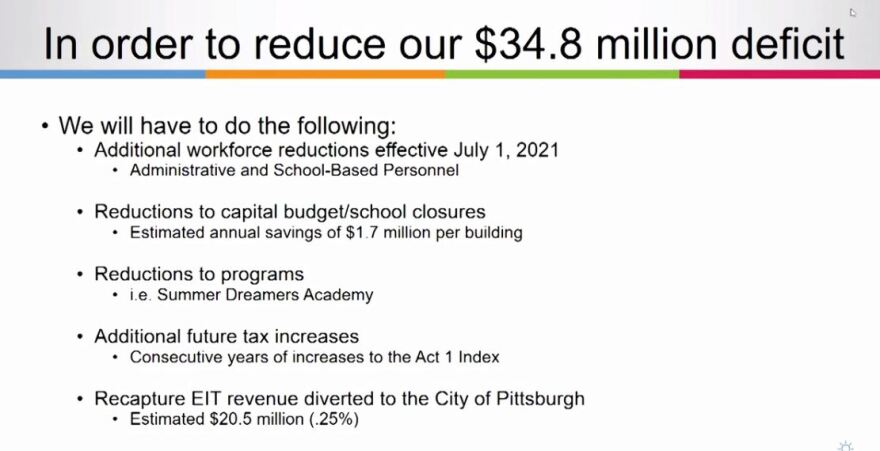

The city’s public school district is evaluating program cuts, workforce reductions and school closures to address its $34 million budget shortfall.

Pittsburgh Public Schools Superintendent Anthony Hamlet told the school board last week that for more than a year his administration has discussed the possibility of closing schools. He said he will now bring the board into those conversations.

“It’s not fiscally prudent for the district to use all of its buildings when so many are underutilized,” he said.

Twelve PPS schools are under half capacity. Another 40 are between 50 and 80 percent capacity. The district has 57 schools and the average age of a building is 75 years. Additionally, overall enrollment dropped by about 800 students in a year bringing the total to 20,438 K-12 students at the beginning of this school year.

“Right now the outlook doesn't seem too great, but we're taking that as a challenge that we have to make sure that we can try to do the monumental task of reducing expenditures and trying to come out better on the other side with still being able to provide the services and resources to our students and provide them with a quality education,” said chief financial officer Ron Joseph.

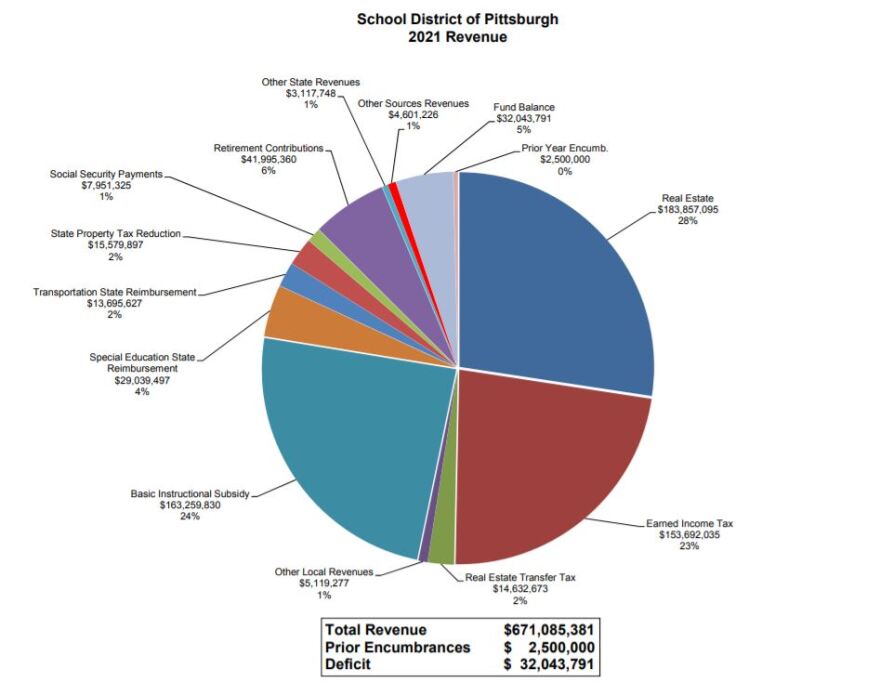

The board has to approve a 2021 budget by the first of the year. The administration has proposed a $668.6 million budget.

It does not include a property tax increase. Last year, the board approved a 1.2 percent property tax increase to help chip away at the shortfall. A city property owner is now taxed $950 by the school district for every $100,000 of a property's assessed value.

Board member Devon Taliaferro said that because some schools are better at “getting additional funding to meet the needs of students and families” she is concerned about equity.

“What I’d hate to happen is that we just close schools that are under-performing. A lot of those schools will be in Black neighborhoods or the majority of the population will be Black and brown students. That’s not the direction we want to go,” she said.

At a budget workshop last month, board member Cindy Falls said that realistically the board has to talk about redistricting – or consolidating schools.

“We can no longer do things the way we used to do them,” she said. “We don’t have the money.”

The state’s second largest district gets a considerable amount of money per pupil from the state compared to other districts. Advocacy group A+ Schools has asked the district to provide an actual cost per pupil school-by-school to better understand how resources are distributed.

Joseph said he thinks the district should get more funding from the state.

“We know that special education may not be funded at the level that it [should be]. We know that there are probably some issues with the charter funding formula that probably could provide relief to districts across the board.”

Board member Pam Harbin echoed that concern. While the administration’s proposed budget does not include a property tax increase, Joseph did tell the board that is the only tool it has to increase revenue.

“I’m not saying we shouldn’t also cut expenses,” Harbin said. “But at some point you have to say what are we losing by not using the one tax mechanism we have to use?”

What changed?

As of last month, 5,023 Pittsburgh students attend 37 charter schools including 10 approved by Pittsburgh Public Schools, a 336 student increase from 2019. In Pennsylvania, charter schools are funded by payments from the school district of residence. The public school district receives state funding and then sends a portion of that money to schools that teach Pittsburgh students.

Those costs have grown significantly over the years. About $102 million or 15 percent of the PPS 2021 budget goes to charter schools.

Special education costs have also grown and account for about 13 percent of the budget.

“I can’t point to one specific thing, our costs are going up across the board,” Joseph said. “We do have a large infrastructure that we have that does require a lot of additional spending such as our cost to maintain our buildings. We probably do operate more buildings than we should be operating so that’s one thing that leads to our cost.”

Other costs have dropped this year because students are learning remotely due to the coronavirus pandemic. The district, though, spent $10.2 million dollars on technology so that students could learn from home. Much of that cost will be reimbursed.

James Fogarty with A+ Schools asked the board to fund learning hubs. Allegheny County’s Department of Human Services and other groups used federal CARES act money to keep organizations that provide afterschool services open during the day. Students attend their virtual classes in a supervised setting, but funding for those hubs will run out by the end of the year.

“If hubs do not get an infusion of additional dollars by January, many will have to close, pushing children out and creating greater stress for families,” Fogarty said in a testimony Monday.

What to cut

A statewide advocacy group, One PA, wants the district to eliminate its police department.

It asked the board Monday to phase out its 20 police officers over the next two years “through a combination of attrition and reassignments to different, non-police roles both inside and outside PPS.” The district also employs security guards who do not have authority to arrest students. The group wants the district to cap security aides to the current 66 positions. It also wants separate and detailed budgets accounting for how dollars are spent on safety.

The proposed budget includes a nearly $128,000 increase to the school safety budget. About 99 percent of the $7,423,000 security budget is allocated for officer salaries and benefits.

Since the district closed buildings in March, the district’s 22 officers and 66 security guards have been assigned to patrol buildings and to help monitor Grab and Go meal distribution, laptop distribution and other events to maintain masking and social distancing, according to the district.

The district did not respond to requests to answer how officers have spent their time since students have been learning remotely since March.

Paulette Foster with the Education Rights Network, a group within One PA, asked the district to invest in racial bias training, restorative practices and more support services in schools.

She also asked the board and administrators if they would send their own children to PPS.

“If you answered no, or you hesitate in that thought, then I’ll avail oneself to take more time in your decision-making when it comes to re-imagining the school safety budget. For those students, parents and community members who have much to lose with your decisions, we demand that you take more of a vested interest in how these funds are distributed as opposed to being used to the status quo,” she said.

During a recent budget presentation, Joseph told the board that the district would save about $1.7 million a year for every school it closes.

Another solution is to “recapture” tax revenue that was diverted to the City of Pittsburgh when the city was struggling financially. Both the City of Pittsburgh and PPS charge an earned income tax on city residents. Fifteen years ago when the city was on the verge of financial collapse, state legislators began diverting some of the district’s revenue to the city. Last year the district sparked controversy when it first suggested approaching the City for reimbursement of what the district estimates to be about $20.5 million.

The board is expected to vote on the budget during its Dec. 16 meeting. It can be streamed at pghschools.org.