Some migratory birds need the deep, dark cover of Pennsylvania’s forests to breed. But natural gas development has cut into their habitat.

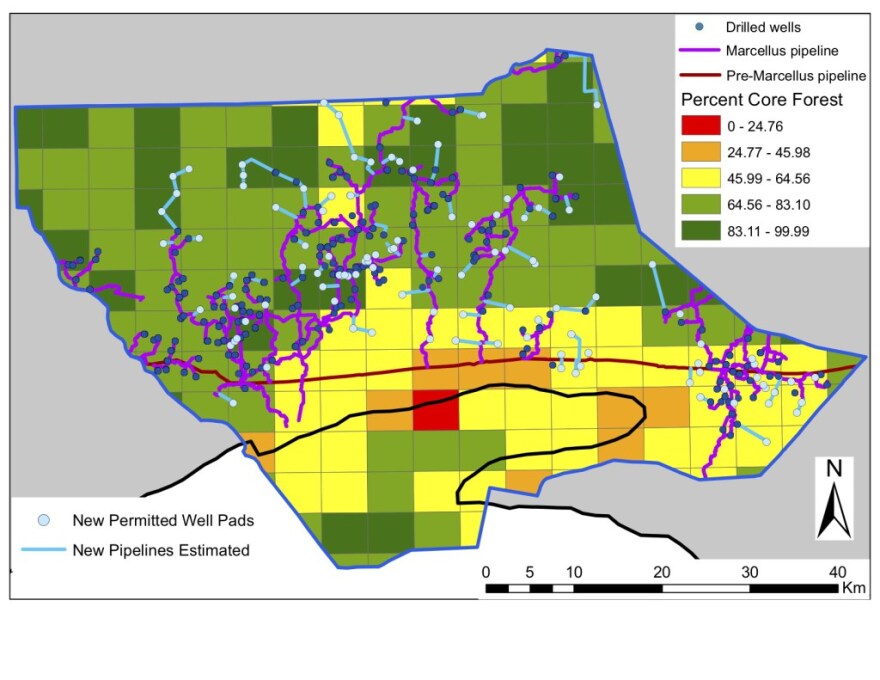

And it’s prompting a call for a mindful approach to pipeline construction. Lillie Langlois is a researcher and instructor at Penn State University, and she studied aerial images to map natural gas development in Lycoming County over a number of years. Langlois and her colleagues found that linear infrastructure like pipelines and roads had a bigger impact on carving up forests — and affecting the wildlife habitat within them — than the drilling well pads themselves. Kara Holsopple talked to Langlois about the study.

Kara Holsopple: Can you describe the area in Lycoming County that you looked at for this study. What’s the forest like there? And what’s the Marcellus Shale industry like there.

Lillie Langlois: It’s the Allegheny Plateau region, so a lot of deep valleys, a lot of steep mountains. And the forests are pretty much contiguous because there’s very few people living there. There’s a relatively limited road network. So you have these hotspots of wildlife that you don’t find in other parts of Pennsylvania. Timber rattlesnakes are quite abundant but rare in the rest of the state. So you have lots of bear, deer, turkeys etc. living in this continuous forest.

Prior to shale gas development there were some activities in terms of logging, in terms of recreational activities. It’s beautiful; people love to go there for canoeing, hiking, snowmobiling – you name it. But over the last eight to 10 years things have changed a bit in the sense that they expanded a lot of the roads that used to be there that were basically hidden and impassable by most people. And now there are two lane highways that two semis can pass each other because that’s what the shale gas industry required to build their infrastructure up there. They really needed a pretty large industrial road network to get back into the woods.

When I first started it was right during the boom in 2011 and 12. And that’s when just your normal everyday country road up there was nonstop traffic 24 hours a day even at night and then things have slowly tapered off. And since 2015, very little activity has occurred. Only recently, in the last six months, do we see drilling activities resuming again.

KH: And you found the forest fragmentation from these roads and also pipelines is the major threat from the Marcellus Shale industry to this forested area. What do you mean by fragmentation?

LL: Basically chopping up a large block of forest into smaller and smaller pieces. It might not look fragmented from a human perspective because we can cross that road and go from one patch of forest to the next. But other species wouldn’t necessarily be brave enough or have the mobility to do that. So if you have a flying squirrel — this arboreal nocturnal creature — they stay within the trees and they’re not going to physically be able to cross that gap of a large widened corridor.

These roads were expanded to 40 – 60 feet depending on the type of pipeline and whether there’s a road in a pipeline together. So it’s the breaking up of one large continuous back into smaller pieces, and when you do that you change the dynamics of the forest. And by that I mean a forested edge where you have that road — you now have increased solar radiation to the edge and that changes the microclimate so now you have drying out of the soil. It’s no longer what used to be contiguous forest where that sun didn’t hit the forest floor and it didn’t have the wind blowing in desiccating the soil which changes your invertebrates and there’s a whole chain effect. I specifically focus on birds and if the invertebrates are lower in density near the forest edge then they won’t go to those areas to feed.

KH: I was reading in your study that there could be higher rates of predation along these forest edges.

LL: That’s right. I mean if you’re out there in the middle of the forest bushwhacking through lots of thick mountain laurel you will appreciate these roads and you will use them to travel because it’s so much easier. And a lot of predators use it for that same reason. So you’ve got grey foxes and raccoons, and along the edges is where they can penetrate the forest and find a nest eggs young, etc.

We focus on the neotropical migrants — they’re migrating here from Central and South America, thousands and thousands of miles, They take months to make this journey and they come to Pennsylvania specifically, and they rely on these large blocks of forest away from people, away from predators, and they breed there. Their success can be impacted by fragmentation and other human disturbance.

KH: One of the interesting things about your study is that you found there was a difference between gas development on private and public land. What is the difference and what is the impact on forests?

LL: So in this area, within our case study of Lycoming County about one third of it is public land. But there was a similar amount of development in both. So we were able to make this comparative study between the two and look at the systematic approach for how they built and created their infrastructure between the two landowners.

We found that public land — they hold the gas operators to a much higher and stricter level in the sense that they won’t let them build the pad anywhere. They are a huge land owner so they have a lot of leverage. It’s not just a small private landowner that will say OK sure you can put the pad on my property or not. They would say, “you can put it in this region but you cannot put it in this area because it’s too close to this wetland. It’s in this view shed so people will see it from below. We want to keep tourism high in this area. We don’t want people to see it from Pine Creek Valley when they’re down there fishing.” And they also had more consolidation of infrastructure so they had more wells per pad than what you typically find on private land owners.

DCNR specifically is who we worked with the closest, and they have a whole team of geologists, foresters, lawyers working on behalf of coordinating gas development on public land. And they were able to negotiate higher number of wells drilled per pad because you can have up to 15 – 20 wells per pad.

KH: So if you had more pads than you would need fewer roads and fewer pipelines because they would all be in one place and you wouldn’t need to spread them out?

LL: That’s right. You’re able to limit the surface disturbance but still have long, lateral lines going strategically in different directions underneath the soil and being able to extract the gas from a similar amount of area. And the other thing they did is they required, whenever possible, to consolidate roads with pipelines.

Because pipelines themselves are the largest portion of the industry’s footprint — about 50 percent of the footprint is from the pipeline itself — and then once you add the roads, you’re up to 70 percent. If you combine those [by placing] a pipeline next to a preexisting road, then you’re sort of killing two birds with one stone in the sense that you already had a fragmenting feature. It might have been a smaller, narrower road that was less of a barrier from animals. But you put that pipeline next to it and instead of creating two separate corridors that are essentially parallel to each other, you put them next each other and you create one larger corridor.

The tradeoff is less surface disturbance. And we see that occurred almost across the board — 70 to 80 percent of pipelines on public land were co-located with some sort of existing feature whether that was a road or some other electrical transmission line. Whatever they could do they consolidated them.

Find this report and others on the site of our partner, Allegheny Front.