Ever since I was a kid, my dad would tell me how he watched two atomic bombs explode when he was in the military. But this past winter over a late breakfast at Denny’s, he mentioned the year — 1953.

So, I did a little bit of digging and learned on May 25, 1953, he was part of a mostly forgotten historic event that had immense foreign policy implications. 70 years later, he may be one of the last living witnesses to Operation Grable. This is his story.

The boy waited patiently in front of a locked gate at a place known as Site W in Hanford, Washington.

He knew he couldn’t go inside, but was excited to see his father — even if it was only during a work break.

As his dad passed through the checkpoint, the 12-year-old’s gaze was fixed upward, on stone-faced soldiers in guard towers. They were gripping .50 caliber machine guns.

Noticing his son’s wide-eyed stare, George Lambert — who was on the construction crew — leaned down and whispered to his boy, Tom, “They just put those up. Something big must be going to happen.”

Something big was an understatement.

Within months in the summer of 1945, the world’s first atomic test took place using plutonium made in the top secret complex, bustling with activity beyond those locked gates.

The clock ticked toward 8:30 a.m.

The Nevada desert air was comfortable at around 58 degrees.

The countdown blared from loudspeakers:

“Ten. Nine. Eight…”

Army Private Tom Lambert tugged at his helmet as he hunched down in the trench. The 20-year-old from Shanksville was one of 2,670 troops positioned around Frenchman Flats outside Camp Desert Rock, a remote testing ground about 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

It was May 25, 1953.

Many likely had no idea they were about to become part of a pivotal moment in the early days of the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

Lambert was ordered to get ready.

The nervous chatter was dwarfed by a distant blast from an artillery cannon.

Only this wasn’t an ordinary cannon, nor was this an ordinary shell.

Seconds passed.

Some held their breath.

Then, a massive explosion echoed in the desert.

An officer yelled, “Get up! Get up! Look at the mushroom.”

It was 2.8 miles away.

Within minutes came another command.

“Move out!”

No longer a sightseer, Lambert clambered out of the dirt shelter and walked toward no man’s land.

Drafted into service

Three months prior, he was living with his parents in Somerset County and building a cabin with his dad.

But with the Korean War at a near-stalemate, the U.S. was still drafting young men into service.

George Lambert delivered the news on a chilly January day, as they sawed lumber.

“You get the mail?” Tom asked.

“Yep. You’re going February 17th,” George said calmly. “Your mother is at home crying.”

George was no stranger to the military, having served stateside during World War I. Later, he worked on a crew that helped build the Pentagon. He then joined tens of thousands of construction workers at the massive Hanford Site in Washington state. That’s where the plutonium used in the 1945 Trinity nuclear test and in the second atomic bomb dropped on Japan — at Nagasaki on Aug. 9, that year – had been made.

Lambert caught the bus to Pittsburgh where he was sworn into service. After a train ride to Fort Meade, Maryland, he learned he would join the Third Armored Cavalry Regiment — the Brave Rifles.

Basic training at Camp Pickett, Virginia, molded him into a soldier.

As Lambert adjusted to military life, the country faced geopolitical pressures that went far beyond the Korean War.

The atomic age was in its infancy, eight years removed from the first atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan. An arms race emerged. The Soviet Union tested a device in 1949, followed by the United Kingdom three years later.

At the time, a nuclear weapon could be used militarily only by a plane. The U.S. wanted more flexibility, so it began developing a small tactical device to be used on the battlefield.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower took office in January 1953, and had campaigned on ending the war.

“The thought behind this was that with America stalemated in the Korean War and NATO forces facing overwhelming conventional forces staged against Western Europe, only the use of small and precise nuclear ordinance could turn the odds in a major conflict,” Michael Hall, former executive director of the National Atomic Testing Museum in Las Vegas, wrote in 2020. “Certainly, President Eisenhower did not want to bankrupt the United States trying to match the Soviets tank for tank and man for man. Small fission or A-bombs and nuclear artillery shells negated the cost of matching the USSR’s conventional forces.”

By the spring of 1953, Lambert would be a witness to whether a small nuclear device could be fired from a cannon.

Its success or failure would change the course of the Korean War and the Cold War in Europe.

Operation Upshot-Knothole

The Atomic Energy Commission set up a series of 11 atmospheric nuclear weapons tests from March 17 until June 4, 1953. It was dubbed Operation Upshot-Knothole. Among its goals was to improve military tactics and training, as well as civil defenses.

The tests would take place among desolate desert and mountainous terrain outside the growing city of Las Vegas at the Nevada Proving Ground — an area that would become the primary testing site of nuclear devices for more than 40 years.

Some 21,000 troops would be involved.

Just a couple of months into his Army stint, Lambert learned he would be one of them.

“I think it was around April that we heard from one of the clerks in the office that we were going to Las Vegas to be in an atomic test,” Lambert said. “We didn’t know too much about it. We knew there was an atomic bomb and there would be a mushroom cloud.”

By mid-May, when Lambert arrived, at least eight of the tests had already been completed. The first, Shot Annie, garnered national attention.

Lambert landed around 3 a.m. on May 19 and got a preview of what awaited him.

“They just told us there’s going to be a test that we might be able to see. It was very, very dark, and an officer came out, a first lieutenant who we didn’t know,” Lambert said. “He explained to us, ‘Now, if you look over a certain way, you might be able to see it.’ When that went off, it got so bright you couldn’t open your eyes.”

He had just witnessed Shot Harry.

“We broke ranks and all of us ran away from the light, and you could feel the heat on your face 25 miles away. It scared the shit out of us.”

That test caused the highest amount of radioactive fallout of any test in the U.S. It would come to be known as “Dirty Harry.”

In six days, Lambert knew he was going to be closer — a lot closer — and there would be no running away.

He would have a front-row seat to true apocalyptic power and be moving toward whatever devastation it left in its wake.

For the first time, a tactical nuclear device would be fired from a cannon — sending an unmistakable message to both allies and enemies.

Foreign policy maneuvering

The firing of the cannon was scheduled to be the next-to-last test in Upshot-Knothole, and the U.S. government worked to make sure no details were held back from the public.

“There were two audiences here. One was the Soviet Union, and the other one was North Korea,” said Martha DeMarre, who retired last January as the archivist for the Nuclear Testing Archive and worked for the Nevada National Security Site for more than four decades.

“Think about how Trinity (the world’s first atomic test) was in 1945. This is 1953. Think how short that period of time is that you could have a shell that would fit in a cannon,” she said.

For comparison, the bomb used in the 1945 Trinity — dubbed The Gadget — weighed 8,000 pounds.

But in those eight intervening years, scientists managed to shrink a device to a weight of just 805 pounds.

“The cessation of hostilities in the Korean War was July 27th, 1953. So, think of the timing there,” she said. “The U.S. had a tactical weapon that could be deployed on the field and it could be deployed to Korea. It could be deployed to Europe.”

It would be delivered by a conventional — albeit unique and massive — weapon: the largest piece of mobile artillery ever built by the U.S. It was a 280 millimeter cannon — 88 tons of steel and firepower.

It would become known as “Atomic Annie.”

Shot Grable

The Atomic Energy Commission and the Department of Defense issued nearly two dozen press releases in the run-up.

One of them stated, “A heavily loaded freight train will chug north this afternoon from Fort Sill, Oklahoma…..aboard will be two of the Army’s new 280mm heavy artillery guns. One of which will soon fire history’s first atomic shell to be launched from an artillery weapon.”

Another release issued by the commission and the Department of Defense laid out the route the big gun would take on its way to and after arriving in Las Vegas:

“The convoy will leave Nellis Air Force Base at 8:30 a.m.(PDT), Saturday, May 9. The convoy will travel south via Highway 91 through North Las Vegas, coming down North Main Street to Bonanza Road, then turning right under the underpass to Highway 95 over which it will continue on to the Nevada Proving Grounds.”

Even Tom Lambert’s hometown newspaper included a little blurb saying he and another Shanksville soldier would be part of the nuclear test.

At the site, Lambert and his fellow soldiers attended classes and watched films on nuclear energy and weapons. Two days before the test, they went into the field in a dress rehearsal of sorts. Soldiers practiced observing the detonation from the trenches, and the maneuvers they would conduct after the shot.

An hour before Operation Grable began, Lambert milled about with his fellow members of the Brave Rifles. They were ordered into their trenches at 8:15 a.m. They were crouched less than 3 miles from ground zero.

“We were watching as they were firing the cannon, but they were firing regular explosives,” Lambert said. “We didn’t get any protective equipment. We had just our helmets and our fatigues.”

Another 4 miles behind the troops sat Annie and a second 280mm cannon.

While Lambert waited on the front lines, Annie was manned by an artillery crew from Fort Sill, Oklahoma. They understood they were heading into unknown territory.

Whatever was about to happen, it had never been done before.

EG&G nuclear testing engineer Barney O’Keefe was a defense contractor that conducted weapons research and development for the U.S. during the Cold War. He was one of two observers for the Nevada Proving Ground stationed with the crew of about 25 men.

He had never seen a weapon that big and admitted he was a little disconcerted by it all.

“I expected to see an elaborate electronic control system, but this was being conducted under battlefield operating conditions. Once the device was inserted, the block would be screwed closed and the officer in charge would fire the gun by pulling on a lanyard, as with any other artillery piece,” he wrote in his 1983 book, “The Nuclear Hostages.”

“I couldn’t believe it, after all our elaborate safety precautions. I wished that I had turned (Nevada Test Director Jack) Clark down and gone home.”

The grim-faced crew prepared the projectile, dialed in the correct setting for time of burst, and locked in the gun’s elevation. They used a panoramic telescope to set the sights.

With the breach closed, they inserted the primer.

The soldiers hurriedly left the gun and took positions in slit trenches.

Shot Grable was locked and loaded.

In the forward trenches, Lambert heard orders over loudspeakers.

“Everyone kneel down in your trench until the command has been given. If you stand up, the intense light may temporarily blind you.”

As the countdown reached two minutes, Lambert and his fellow soldiers were ordered to crouch.

“They told us that it’s gonna be the test and to get ready for it,” Lambert said.

The countdown reached one.

Flame and smoke shot from the barrel as the nuclear projectile hurtled toward its target.

A handful of seconds passed before it burst some 7 miles away and 524 feet above Ground Zero — amid a flash of a blinding, disorienting light that washed away any sense of shape and color.

The shell matched the power of the Little Boy bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

The orange and red mushroom cloud climbed to the heavens — reaching an altitude of 35,000 feet.

“They hollered to us, ‘Get up! Get up! Look at the mushroom,” Lambert said. ”There wasn’t any color to it. It was just like a white mushroom to me.”

Then, he noticed something barrelling toward him in a low rumble.

“We’re standing there and all at once, we see this wave coming across the desert. We kept saying, ‘What’s that? What’s that?’” Lambert said.

His officers warned, “Get ready for the shock wave!”

Two seconds later, a deafening crack.

“When the shock wave hit, everything shook,” Lambert said. “It was just…the whole…I was never in anything like that. Everything just shook and shook.”

Some soldiers yelled for help. The shockwave caused some of the trenches to collapse — partially burying several of them.

“There were some fellas that we had to dig out,” Lambert said. “Nothing serious. We just had to get them out of it.”

They didn’t have much time. Within 11 minutes, they were out of the relative safety of their earth works and beginning their assignment — attacking an area anywhere from 1.5 to 1.8 miles from ground zero.

High level observers

Lambert didn’t know others were watching with great interest. Dozens of federal lawmakers joined Secretary of Defense Charles Wilson, Secretary of the Army Robert Stevens and Admiral Arthur Radford, designated-chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

They were among some 700 observers, including a group of more than eight dozen journalists who reported on the blast from 10 miles away.

They witnessed the detonation from a bit less than 7 miles to the north of ground zero, then moved to where the maneuvers would take place.

“After the test, the radiological safety team went in to check the levels so the congressman could come in and look at what was going to happen. They actually witnessed the military coming out of their trenches and heading off to do their maneuvers,” said DeMarre, the retired Nevada National Security Site worker. “This was critical to show the Soviet Union that we could do this device and get right out there and fight.”

Secretary Radford said he considered the test a milestone in the history of atomic weapons.

“The artillery shell now becomes the companion piece of the tactical A-bomb … Thus the single A-shell explosion in Nevada may have accomplished all that was sought for the weapon,” wrote Dick Pearce of the San Francisco Examiner. “The Russian knows now that the shell exists for use against him; he will not willingly provide a situation for its use.”

EG&G nuclear testing engineer Barney O’Keefe — who never believed in tactical nukes — was aghast at the power unleashed by the big gun.

“What of the soldiers on a battlefield? The first flash would sear the eyeballs of anyone looking in that direction, friend or foe, miles around. Its intensity cannot be described; it must be experienced to be appreciated,” he said.

Ground zero

But the geopolitical perspective on the blast wasn’t of concern to Lambert. He was watching for rattlesnakes as he moved through the desolate ground and brush.

He and his fellow soldiers appeared to have made it as close as 765 yards, or less than half a mile, to the south of ground zero. They could see an area as close as 500 yards to the impact zone.

“They came to us with Geiger counters and said, ‘All right, this is as far as you can go,’” Lambert said.

Buildings, houses, military equipment, vehicles and trees had been built or placed in certain locations at certain distances from ground zero to test how they would absorb the blast.

It was unlike anything he had ever experienced.

“I saw a brand new school bus that was turned over,” he said. “There were cement buildings impacted too.”

But, more disturbing to him were the animals that had been placed close to the blast zone.

“We saw several sheep that had burned wool on them. I still remember the sheep,” Lambert recalled. “They also told us they had rabbits fixed to keep their eyes open when the light came to see how they’d react.”

Martha DeMarre notes a concern at the time was that a person could be blinded by a nuclear weapon.

“So, they looked at various tests over the years of the thermal effect on the cornea,” she said.

Mice and pigs were also tested in order to gather bio-medical data.

“The animals did not fare very well in Grable because the effects were so much more than they had estimated. Very few were in conditions to really advance the knowledge,” DeMarre said.

High winds and dust soon became a problem, forcing a premature end to the maneuvers — after only about an hour.

It was all over by noon and seemed anti-climatic to Lambert.

“We went back to the bus and were taken to our tents,” he said. “When we got back to the 14-man tents, several of them were blown over.”

His work in the desert was also over. He and the members of the Brave Rifles returned to Camp Pickett the next day.

But, what Lambert experienced was a further cementing of the United States as a world superpower.

“After World War II, the United States’ position in the world was much different than it was before World War II. This was the announcement, ‘Yes. We’re here to stay. Don’t step over the line,’” DeMarre said.

But at Camp Pickett, no one asked Lambert about the test.

He just went back to his normal duties.

70 years later

Shot Grable’s impact is still being felt today. North Korea’s nuclear weapons program has produced a small stockpile. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine stalled and turned into a slugfest, President Vladimir Putin began hinting it may consider using tactical nukes.

“North Korea will never, in my opinion, never give up those weapons. They want to be on equal basis as the other superpowers,” DeMarre said. “If you have a nuclear weapon, nobody’s going to attack you, because there is the risk of nuclear war.

“Russia is trying to change the dynamics (in Ukraine) by talking about nuclear war and tactical nuclear weapons. So it all goes back to basically the first tactical nuclear weapon, which was the cannon.”

***

After his time in the Army, Lambert left Shanksville for a job at J&L Steel in Aliquippa and got married.

He and his wife, Helen, raised two boys.

After 30 years in the mill, Lambert retired — just as the steel industry collapsed.

More than a decade of his golden years were spent caring for Helen, who died in 1993 after battling Alzheimer’s Disease.

Lambert moved to New Cumberland three years ago to be closer to family — leaving behind his home of 57 years in Aliquippa.

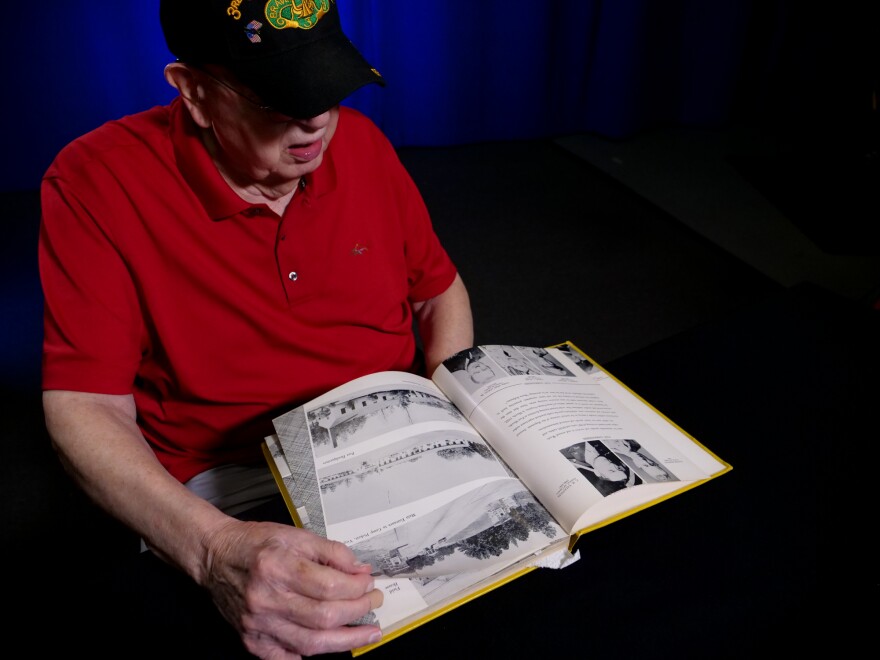

Now 90-years-old, Lambert may be one of the last surviving participants in Operation Grable.

He spends most of his time watching old westerns on TV. He doesn’t drive anymore and uses a walker to get around.

He embraces his military service, often donning a baseball cap sporting the Brave Rifles insignia for the 3rd Cav.

He also recently started watching videos from that day in 1953, marveling at the power of Atomic Annie and lamenting how he never had a chance to see the big gun up close.

Not one for reflection, he has come to understand what he was a part of in the desert 70 years ago.

“You didn’t realize what an historic moment was at the time, but then over the years, you realized what it was like. I’m proud of being a part of the testing. I was always proud of it. When I watch the videos of the cannon firing, it’s just a wonder anyone survived. Who would have ever thought that someone from a little town like Shanksville would end up in Desert Rock, Nevada, in an atomic test?”

But it’s not all pleasant memories.

He has often wondered if his bouts of skin cancer and prostate cancer were related to his time in the desert.

But, neither of those diseases are on the Department of Veterans Affairs’ list of 21 “presumptive cancers,” which helps determine any benefits he would receive.

The federal government has had a checkered past in helping atomic veterans, downwinders, nuclear weapons workers, and others as thousands of participants dealt with illnesses related to radiation exposure.

The issue is still being fought over today.

In July 2022, the Defense Department approved an Atomic Veterans Commemorative Medal to recognize the “service and sacrifice of veterans who were instrumental in the development of our Nation’s atomic and nuclear weapons programs….”

Lambert and other vets are eligible to receive the medal for participating in the testing and development of the country’s nuclear arsenal, as well as an Atomic Veterans Service Certificate.

But within the notification documents are a hedge. It states, “Award of the Atomic Veterans Commemorative Service Medal and the Atomic Veterans Service Service Certificate is not intended to, and does not, confer any right or benefit, substantive or procedural, enforcement at law or in equity by any party against the United States, its departments, agencies, entities, or officers.”

Lambert received his medal and certificate this summer.

They are on display on his bedroom dresser.

Read more from our partners, WITF.