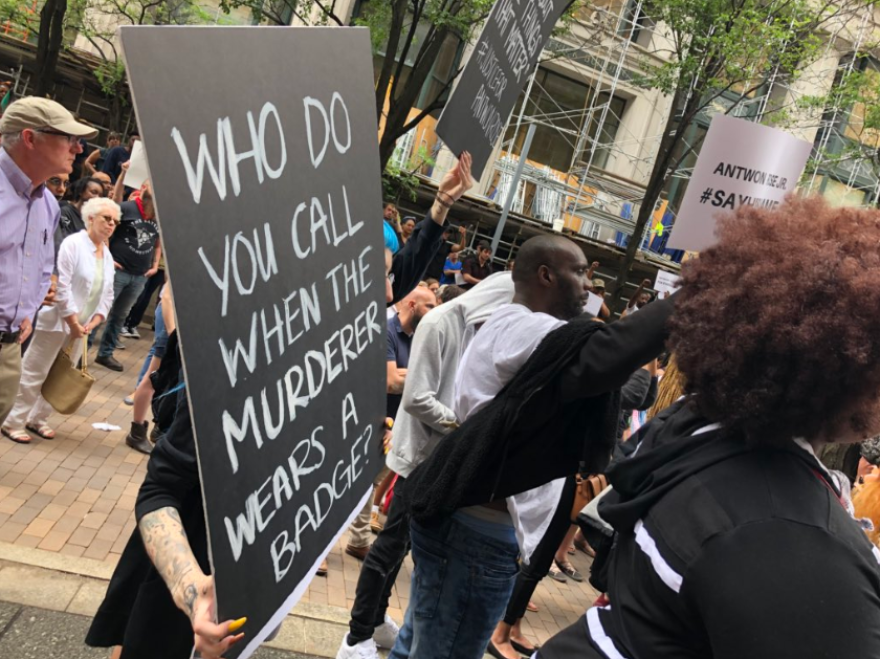

The city of Pittsburgh issued new rules for protesters late Thursday afternoon – releasing a new policy that seeks to limit protests that have shut off area streets since the police shooting of Antwon Rose last month.

Protests have largely been non-violent, if disruptive. But “we’ve had cars going through crowds and protesters surrounding vehicles,” said Chris Togneri, a spokesman for the city’s police bureau. “The goal here, while respecting everyone’s First Amendment rights, is keeping people safe.”

While affirming that the city “completely supports the right of people to protest," the policy identifies numerous intersections and roadways where unpermitted protests will not be allowed to block traffic.

The most critical arteries are identified as “Red Zones,” and include prominent roadways like the Parkway East – where an early protest shut down traffic for hours – state Routes 28, 51, and 65, and other thoroughfares like Allegheny River Boulevard and the 10th Street Bypass. Tunnels and bridges are also on the list, as are hospital entrances.

The individual “Red Zone” intersections are concentrated Downtown, and include such chokepoints as Grant Street and the Boulevard of the Allies, where an earlier protest did stop traffic during the latter part of the morning rush hour.

Another seven thoroughfares are identified, along with school zones, as “Yellow Zones” where unpermitted protests will not be permitted to block traffic during rush hour (from 7 a.m. to 9 a.m. and from 4 to 6 p.m.). Traffic blockages in these areas will be limited to 15-minutes at other times. The roadways include such high-profile Pittsburgh roads as Carson Street, Smithfield Street, and Liberty Avenue.

"Because we've been allowing things to occur, we felt it was important if we're going say 'you can't do this,' we want to tell you this is what we're doing," said police chief Scott Schubert Friday morning. "So we want you to know what we're doing and why we're doing it. And it all comes down to safety."

The policy spells out a process for dispersing protesters if they run afoul of the rules. Police must first try to speak to protest leaders and ask them to leave, identifying an alternative location if possible. If that fails, police are to broadcast an initial dispersal order and then a second one five minutes later, if necessary. If protesters don’t leave within 3 minutes of that second order, a final warning is given “as the crowd management officers begin to move in to clear the violators.”

Police will respond immediately in the event of violence, the policy adds.

“Mass arrests should be avoided unless absolutely necessary,” it concludes. “Instead, targeted arrests of protesters and/or clear leaders should be prioritized.”

The new approach comes after numerous protests have disrupted traffic in various parts of the city, including Downtown, the South Side and the North Side. Some protests have involved potentially dangerous confrontations between protesters and motorists.

"As the protests have continued on for the past five weeks, we've had serious concerns about public safety," said Public Safety Director Wendell Hissrich. "It's becoming more and more problematic. ... It's really come to a head over the past several weeks with the incidents that have occurred."

Demonstrators were not consulted on the rules: Hissrich said "We have invited the protesters to come to us, and we would cooperate with them." But there has been only limited interaction he said, and "The lack of cooperation puts the public at risk."

A protest is already scheduled for 10 a.m. Friday outside the Allegheny County Courthouse, though it remains to be seen whether it tests the new policy. Previously, demonstrators have not sought permits, and have generally kept their plans under wraps. The Friday gathering, by contrast, was announced in a press release sent by more established activist groups.

The city devised the policy with consultation from the ACLU, whose Pennsylvania legal director, Vic Walczak, praised the policy.

“It’s pretty remarkable what this administration has done has done in terms of free speech,” said Walczak, who said he had never seen such a policy for unpermitted marches before. “When I think about what it was like 15 years ago when we had to sue them over this stuff, it’s a far cry better from that.”

Walczak said that the restrictions are constitutionally permissible, because they regulate not the content of the speech, but only the conditions under which it takes place – and because there is a legitimate government interest in doing so.

Walczak says that in the case of unpermitted marches, the city didn’t have to issue a policy at all from a legal standpoint – but that doing so is wise.

Handling the protests is “a bigger political issue than a legal one,” Walczak said. “If I walk out in the middle of Grant Street and hold up a sign, blocking traffic, that’s called obstructing a highway. The problem is the spectacle of arresting people" -- especially given the sensitivity of police-community relations. Rose, 17, was unarmed when he was shot by East Pittsburgh police officer Michael Rosfeld, who is facing a charge of criminal homicide.

WESA reached out to some protest leaders Thursday afternoon, but did not receive an immediate response.