County officials called the 2020 election the perfect storm. In Allegheny County, officials were tasked with running a high-stakes election while making sure an unprecedented number of voters could safely cast their ballots.

They had to implement a new mail-in voting law during a pandemic. Plus, the whole country was watching closely, because Pennsylvania was a crucial swing state. To pull it off, local officials built a brand-new system to process hundreds of thousands of mail ballots.

During the summer of 2020, as the U.S. Postal Service said it would likely struggle to meet the fall election’s deadlines, officials were formulating plans to open what they called satellite voting locations. But now, as another high-profile election approaches, local officials say that strategy is too expensive to repeat.

“It was needed at that time,” said Jen Liptak, chief of staff to the county executive. She was one of many county employees who worked on election plans.

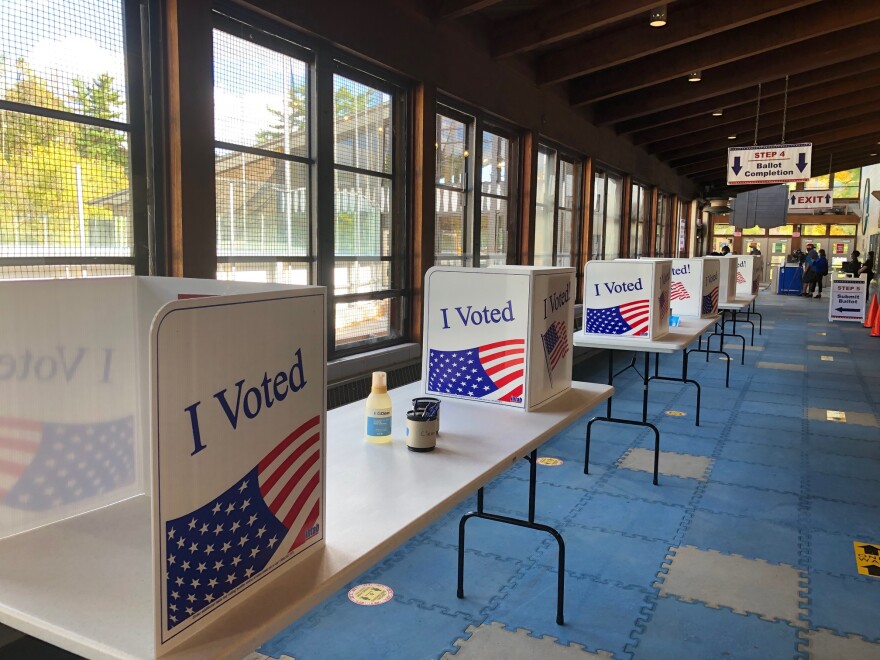

The nine locations were open only on weekends in October. But they allowed nervous voters to drop off their own completed mail ballots in person. Or, they could do what’s sometimes called “over-the-counter voting” — where you walk up to the front desk, request a mail ballot, vote and return it all in one trip.

“We had the new law, we had COVID, confusion,” Liptak said. “People wanted their votes counted. They were concerned about going into the polling places. And that's why it became essential. So that cost, whether it was human capital, whether it was financial, it was needed right then and there.”

The numbers show their efforts did pay off. Allegheny County director of elections Dave Voye said about 6% of the county’s votes — or 42,000 ballots — were cast at these satellite locations ahead of the presidential election.

“I can't explain how busier we were than normal,” he said. “I mean, normally, you'd have maybe five or six people at the counter. We had lines down the street in the 2020 [election].”

But the county will not be offering satellites this year. Voye said turnout typically isn't as high in a midterm election, and because vaccines are widely available, COVID-19 is less likely to keep voters away from the polls.

His boss, Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald, agreed.

“Those 42,000 ballots can be done in other ways,” Fitzgerald said. “By sticking it in a mailbox. So, it's not like those 42,000 people wouldn't have been voting otherwise. And we're seeing already it seems that people are getting more used to the mail-in ballots. so the more and more it gets used, I think people will feel comfortable with it.”

Satellite voting wasn’t cheap. The county paid $469,574.87 to operate the sites — out of $13,773,041 in total election costs. A county spokesperson noted that the county was able to help cover costs through pandemic-related funding including the CARES Act, as well as an election security grant.

The satellite voting project was a logistical nightmare. Officials ended up having satellites at such places as a county ice rink — not exactly spots that were suited for a highly technical operation. Some spaces had only one electrical outlet.

Fitzgerald, who chairs the county board that oversees election activity, also says there’s a human cost to consider.

“The staff can only be stretched so far. So they're running polling places, you know, the 1300 polling places, plus all the mail-in balloting which is occurring in high numbers, and then you take those staff to try to staff other places...you're stretching the system to a very difficult endeavor,” Fitzgerald said.

But another Democrat on the elections board believes that voting access should be expanded no matter the cost.

“$500,000 in the grand scheme of increasing access for people to vote and increasing confidence in our electoral process — to me, I don't think you can put any price on that,” said County Councilor Bethany Hallam. She worries about the optics of pulling out all the stops only during presidential elections.

“It is really disheartening to see that we have voters who had this great option for how to vote, basically put in front of them and then ripped away as soon as it was given to them,” she said.

Such a decision could signal to voters that other races in other cycles are less important, Hallam said. This year’s election, for example, could flip control of the governor’s house and the U.S. Senate — races that could play a huge part in reshaping election rules for 2024.