After a train derailed in East Palestine, Ohio, last year, and chemicals were released throughout the community, the National Transportation Safety Board investigated what happened and why.

The agency will hold a meeting on Tuesday to vote on its findings. One major issue is whether Norfolk Southern provided all relevant information to decision-makers as the disaster unfolded.

What happened?

The Norfolk Southern train derailed in East Palestine on Feb. 3, 2023, a Friday night, and fires flared up from the smoldering tank cars through the weekend.

A Unified Incident Command quickly formed. It included Norfolk Southern, emergency responders, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, and was led by East Palestine Fire Chief Keith Drabick.

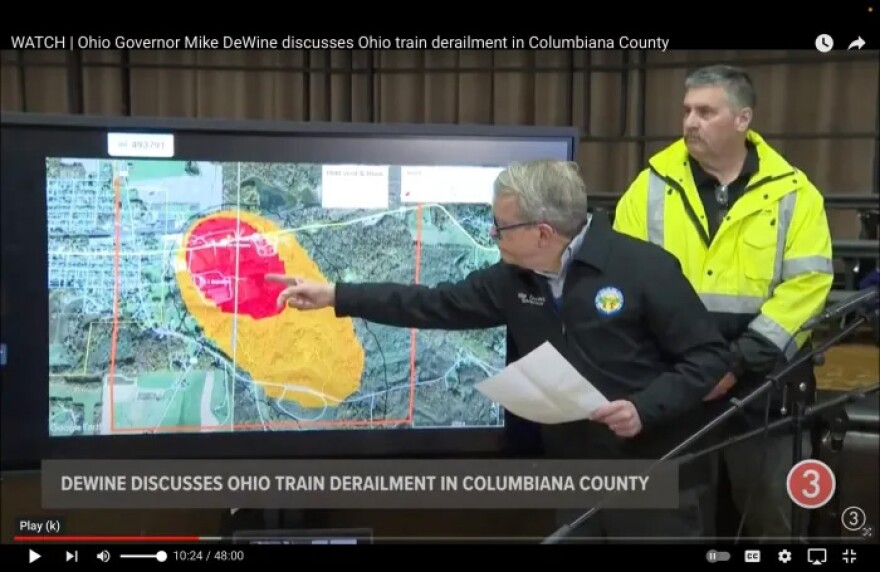

That Monday, Drabick stood behind the governor at a press conference, as DeWine explained why he and Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro were issuing mandatory evacuation orders for residents in a one-by-two miles radius around the derailment site, more than 2,000 people.

“The vinyl chloride contents of five rail cars are currently unstable and could potentially explode, causing deadly disbursement of shrapnel and toxic fumes,” DeWine said.

He then pointed at a map with a red circle outlining a one-mile radius around the derailment site: “Those in the red area, those in the red area are facing grave danger of death. Those in the orange area are at severe risk of injury, including skin burns and severe lung damage.”

DeWine explained that to avoid this, they would vent the vinyl chloride, a carcinogenic chemical, from the cars and burn it off.

But that afternoon, during the vent and burn operation, an explosion occurred, and a huge dark plume was seen for miles around East Palestine. It left ash on people’s lawns and cars and chemical contamination throughout the community.

So, how did the Unified Command decide that the vent and burn was necessary?

The NTSB held hearings in East Palestine last summer, investigating issues such as freight car wheel bearings, railway defect detectors and the timeline of the emergency response efforts.

Norfolk Southern’s director of hazardous materials, Robert Wood, testified that one of the vinyl chloride cars seemed to be going through a chemical process that they feared would blow up the car.

“We observed what we believe to be multiple signs of polymerization in the tank cars carrying vinyl chloride,” Wood said.

Norfolk Southern hazardous materials contractor Drew McCarty testified that one of those signs was the rising temperature of that car.

That Sunday, a fire near the car had gone out. When he first checked, the temperature reading was 135 degrees Fahrenheit. Over the next hour, it rose to 138 degrees.

“So in that snapshot of time before we met with the Chief and his staff, it was trending upward,” McCarty said. He testified that there was only one option to deal with it.

“And all data resources, and all of our combined experiences, had us with a legitimate concern for polymerization and lack of tactical options except vent and burn,” he said.

Norfolk Southern’s Robert Wood put it this way: “Because of factors that rendered other options too dangerous and potentially ineffective, a controlled vent and burn was determined to be the best and safest action by the Incident Commander, given the circumstances and the information available at the time.”

Chief Drabick, who was the Incident Commander, testified at the hearing that Norfolk Southern provided no other opinions and told him and Governor DeWine that they had 13 minutes to decide whether to approve the vent and burn.

“The final “yes” was given by me based on the consensus of everybody in the unified command that there was no other option,” Drabick said.

But, there were other opinions being presented to Norfolk Southern

Dallas-based OxyVinyls owned the vinyl chloride and sent a team to East Palestine.

Paul Thomas, vice president of health, safety and security for Oxyvinyls, testified that by Monday morning, the temperature in that car had dropped by 12 degrees and was stabilized at 126 degrees.

“It’s conclusive to all of us that polymerization was not going on in that car,” Thomas said.

But that message did not get to the decision-makers.

“We were not part of the Unified Incident Command, and we did not participate in or recommend the decision on the vent and burn operation,” Thomas said.

Preview of the NTSB findings: vent and burn didn’t have to happen

While testifying at an unrelated Senate hearing this past March, NTSB’s Jennifer Homendy was asked by Ohio Sen. J.D. Vance whether the controlled burn was necessary because the rail car temperature had decreased.

“It was stabilized well, well before the vent and burn – many hours before,” she said.

Homendy also explained that there was another option to deal with the car they were most concerned about: “Let it cool down. It was cooling down.”

But Homendy said Norfolk Southern never informed Chief Drabick and the Unified Command of this option.

“Oxyvinyl was on scene, they were left out of the room, the Incident Commander didn’t even know they existed, neither did the governor. So they were provided incomplete information to make a decision,” she said.

Norfolk Southern said in an email that safety was the top priority of everyone involved, and called the vent and burn successful.

The rail company said it stands by the decision to do the controlled burn, as does Governor DeWine and Chief Drabick.

What difference could the NTSB findings make?

NTSB is not a regulatory body, so it can’t write new rules, but it does make recommendations for improving railway safety for Congress and regulators to consider. And while NTSB findings are not admissible in civil court cases, they can have an impact.

Last week, Ohio Attorney General David Yost said he would not sign on to a $310 million federal settlement reached between Norfolk Southern and the U.S. EPA until after the NTSB investigation is finalized on Tuesday so its findings can be considered in the negotiations.

Read more from our partners, The Allegheny Front.