An Allegheny Health Network chemist is developing a longer-lasting version of naloxone, to stop people from slipping back into overdose.

Naloxone is the medication that can revive someone from an opioid overdose. It knocks the opioid molecules off certain receptors in the brain, which stops the drug from taking effect. On rare occasion, the medication doesn’t last long enough, which allows patient's breathing to become so shallow they become unconscious.

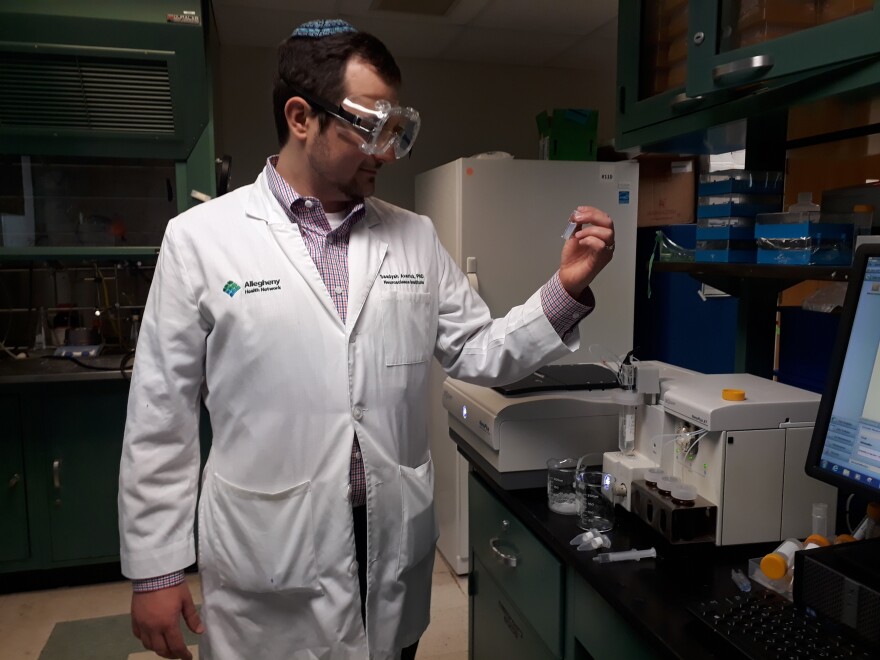

In his lab at Allegheny General Hospital, chemist Saadyah Averick holds up a small vial of tacky, white powder.

“That’s the actual polymer powder of the naloxone polylactic acid,” said Averick,

Right now, naloxone molecules are relatively small and can be metabolized quickly. To make sure the medication works, Averick said people in overdose are flooded with highly concentrated doses. This can cause a harsh withdrawal, which often feels like a horrible flu with body aches, shaking and nausea.

To create a naloxone that’s gentler and works longer, Averick and his team are creating a naloxone polymer, which is a molecule made from joining together many other, smaller molecules. They’re also changing the size of the polymer’s molecules.

“Depending on that size,” said Averick, “you can change the surface area of that material. Which would then allow you to change the rate of degradation and release.”

Averick said that right now he's testing the polymer with mice. If he can get the funding, Averick estimates his longer-acting naloxone might be commerically available in five to 10 years.

Dr. Michael Lynch, the head of the Pittsburgh Poison Control Center at UPMC, said that data show the patients most likely to fall back into overdose after being treated with naloxone aren't those using illicit opioids like fentanyl or heroin.

"There could be a benefit [to longer-lasting naloxone] in certain clinical situations such as an overdose on long-acting prescription opioids," said Lynch via email. "[These] opioids can certainly result in recurrent opioid toxicity after initial reversal with naloxone."

Alice Bell, overdose prevention project coordinator at Prevention Point Pittsburgh, a nonprofit that specializes in drug user health and outreach, agrees with Lynch that a longer-lasting naloxone likely woudn't be needed by most of the people she works with.

“I’m sure there’s some particular overdose cases where this might be useful,” said Bell, “but I would not see this as something that should be generally used in opioid overdose cases.”

Bell said she’s rather see funding go towards making naloxone cheaper and ideally, available over-the-counter.

WESA receives funding from Allegheny Health Network.