It’s been two years since the bronze statue of Pittsburgh-born composer Stephen Foster and a barefoot black man playing a banjo was removed from Schenley Plaza. The statue was denounced for decades, but the criticism gained steam in the aftermath of a deadly protest in Charlottesville, Va. over the removal of Confederate monuments.

The city held public meetings about replacing the Foster statue with one of an African-American woman from Pittsburgh. Two years later, no replacement statue has been erected. A city spokesman declined to provide information about the status of the effort to replace the Foster statue.

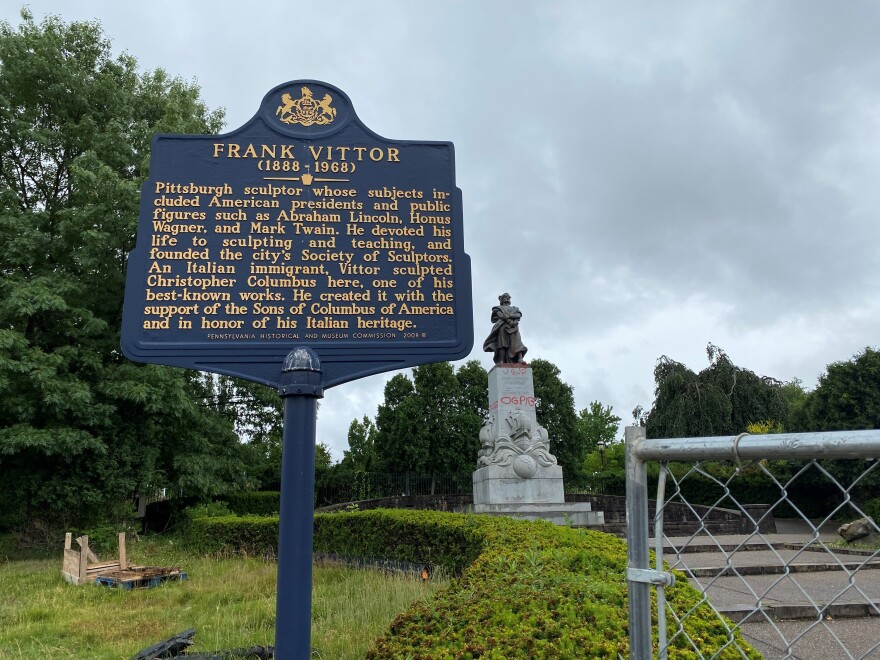

Now, another monument has come under fire: the Christopher Columbus statue in Oakland. Columbus statues in cities across the U.S. have faced public ire, as part of a movement to reevaluate how the colonizer is remembered.

Calls for removal of the statue in Pittsburgh have gained traction on social media. A Change.org petition to remove it has more than 6,000 signatures.

The 50 foot bronze statue can be seen from Frew Street in Oakland. Though the Columbus statue is near Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens, it is owned by the city.

But that doesn’t absolve nearby groups, including Phipps, from commenting on the statue, according to Boom Concepts artist Bekezela Mguni, founder of The Black Unicorn Library and Archives Project. Mguni has repeatedly called for the statue’s removal on social media.

“If any of those organizations that sit around that statue expect to be believed that they have any solidarity with Black and Brown and Indigenous people, they should call for the removal of that statue,” Mguni said. “[Not speaking out is] being complacent.”

The Art Commission declined requests for comment regarding calls for the Columbus statue to be removed. The Commission is scheduled to meet Wednesday, but neither the Foster statue replacement nor the Columbus statue appear on the agenda.

The monument in Schenley Park has been spray painted recently with messages including “OG Pig” and “Murder." It’s been targeted ahead of Columbus Day in recent years as well.

Jennifer Taylor, a professor of public history at Duquesne University who has participated in the City’s podcast on public art, suggests recent acts of vandalism have been beneficial in sparking conversation around Columbus and his place in history.

Statues of figures like Columbus are being criticized alongside those of Confederate generals, according to Taylor. “I think the conversation, particularly northern cities are having a difficult time with, is what to do with white supremacist objects that have no clear tie to the Confederacy?”

People are asking deeper questions about America’s founding, “Indigenous people, colonization, that’s where Columbus fits," Taylor said.

But according to Basil Russo, national president of the Italian Sons and Daughters of America, the story of how Columbus statues popped up across the country is more nuanced.

In 1891, 11 Sicilians who had been acquitted of the murder of a police chief were lynched in New Orleans, La. It was one of the largest single mass lynchings in American history. As part of an effort to ease tensions and appease Italian Americans in the aftermath, the first Columbus Day was created in 1892, 400 years after the explorer first landed in the Bahamas. Statues of Columbus appeared soon after. A federal holiday was established in 1968.

Russo said that historic context has been missing from conversations surrounding Christopher Columbus and his connection to Italian Americans. The statue in Pittsburgh was built by Italian-born Pittsburgh resident Frank Vittor in 1958. Vittor also created the Honus Wagner statue at PNC Park.

“Columbus’ journey launched 500 years of immigration to America, attracting people from throughout the world seeking a better life for their families,” Russo said. “That’s what the Columbus statue stands for to us.”

But not everyone sees Columbus that way.

“For the Indigenous people of this country, Christopher Columbus and celebrating him with holidays… continues to be a slap in the face and disrespect to the truth of their experience,” Mguni said. “Remove those symbols of harm, that’s one way we can begin to repair.”

Mguni said while conversations about monuments of historical figures are important, she believes that it’s a matter of time before people take matters into their own hands and topple the Columbus statue themselves. Monuments of Columbus have been beheaded in Boston and thrown in a lake in Richmond, Va.

According to Duquesne's Jennifer Taylor, these conversations are a symptom of a larger American problem.

“Germany has had to deal with the Holocaust. South Africa has had to atone for Apartheid. The United States has not really systematically addressed slavery, Jim Crow and some of these larger civil rights issues. And that’s why I think we’re battling it out on the public landscape,” Taylor said.