In 1991, the brutal civil war in Liberia caused poet Patricia Jabbeh Wesley and her family to emigrate to the United States. The war splits her story nearly in two: To escape her home country, Jabbeh Wesley has said, she literally had to walk over dead bodies.

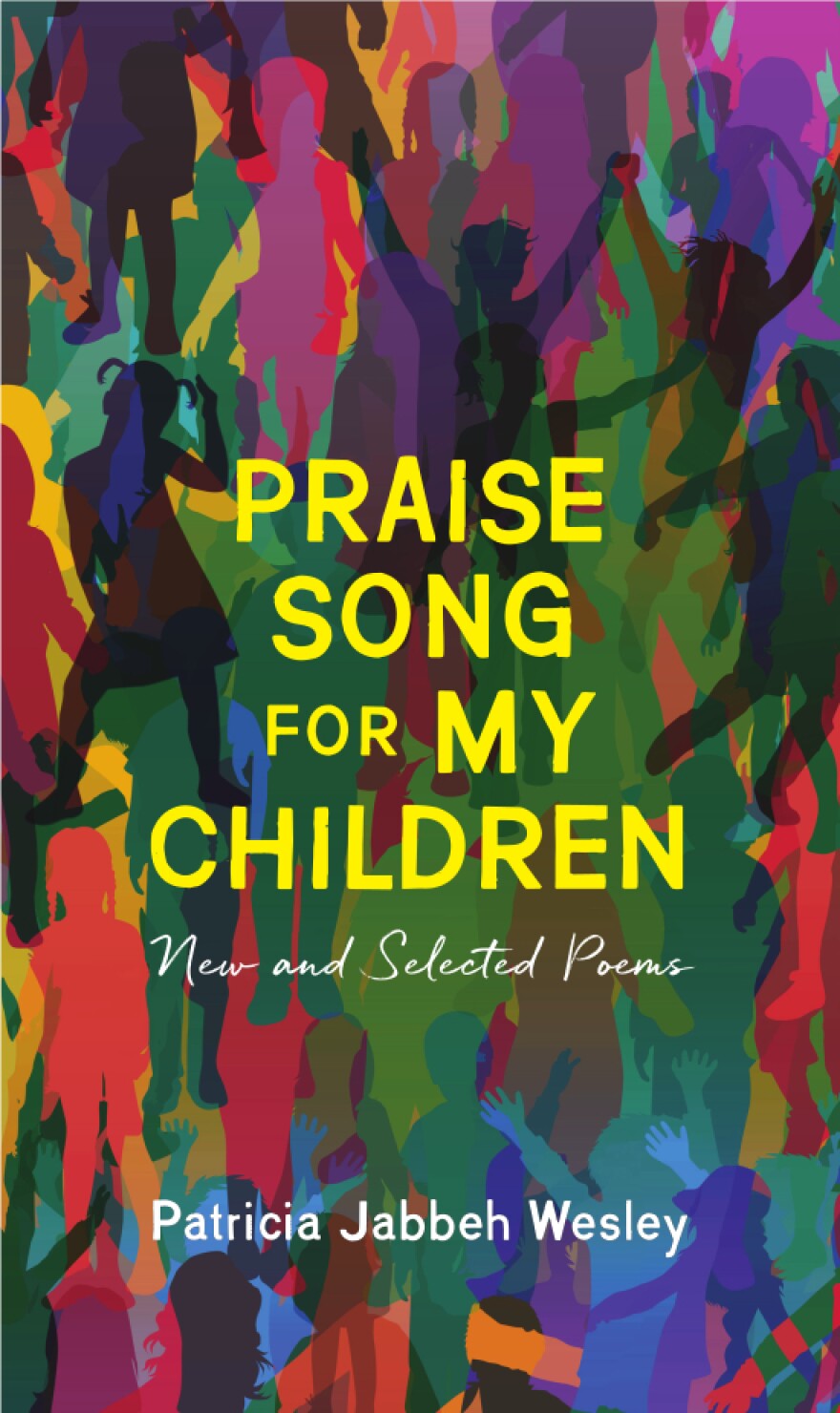

While there is no forgetting such trauma, Jabbeh Wesley has built a career as an educator and internationally recognized poet. Her sixth collection, “Praise Song for My Children,” published by Pittsburgh-based Autumn House Press, includes selections from her first five books of poetry alongside two dozen new poems that continue tracing her trajectory as an African who’s spent the past three decades in America.

Jabbeh Wesley lives in Altoona, where she has taught creative writing and African literature at the local Penn State campus since 2005. Her work has been translated into Finnish, Hebrew, Italian and Spanish, and she has led poetry workshops around the U.S., and in South America and Africa.

The books sampled in “Praise Song For My Children” range from her first, 1998’s “Before the Palm Could Bloom,” to 2016’s “When the Wanderers Come Home.” The subject matter includes family, intimate portraits of village life, and tough evocations of her country’s civil strife. The new poems find her confronting aging and current events, as well. But Jabbeh Wesley remains deeply invested in exploring the meaning of home. In the title poem, she writes:

Let me sing to you, my daughters, you who have,

never known where we come from.

You who will never know your mother’s tongue,

you who have become the metaphor of lost

warriors, who were captured by war.

Let me be your songwriter, the song you sing,

the dirge you do not know how to sing.

A “praise song” is a specific African poetic form, used to communicate everything from praise for heroes or family members, to dirges for the deceased. The form connects powerfully with her heritage. “The entire poem is traditional, the way a grandmother would sing to her grandchildren,” said Jabbeh Wesley in a phone interview. “And a woman would sing to her children at a ceremony.”

"The entire poem is traditional, the way a grandmother would sing to her grandchildren"

Other new poems in the collection address racism in America (solemnly, in “They Killed a Black Man in Brooklyn Today,” and with humor, in “TSA Check”); wrenching childhood memories (“I Saw Men Leaving My Mother”); the dubiety of hope in the face of current events (“After the Election”); and the isolation of American society (“Suburbia”). And family, in a broad sense, remains vital to Jabbeh Wesley, who dedicates the book to more than 100 of the individually named “beautiful young people I call my children & many more.”

But it’s the idea of home Jabbeh Wesley returns to perhaps most frequently. That’s hardly unusual for a poet, but the pull might be even stronger for Africans like Jabbeh Wesley, whose umbilical cord is buried in her home village.

In “November 12, 2015,” she confronts stereotypes about African nations. “No matter how ugly they say home looks, / there’s never a day when you do not want to go back home.”

“I was and thinking of the whole idea of how our countries in Africa and how our homelands are painted by the Western media and the Western world,” she said. “And home is home no matter what people think. If the people are vibrant and happy and resilient and they are wonderful culturally, and if you know that there is something great about where you come from.

“The whole idea that people say Africans is this, Africa is that. There are so many people living in Africa that are happy to live there, even Americans. And so I said to myself, ‘That’s my home.’ No matter how ugly they say my home is, no matter how terrible it may seem, that's where I come from. And my history and who I am, and what makes me tick, is African.”

"My history and who I am, and what makes me tick, is African"

The relationship is complicated, though. In “At the Borderline,” she recounts a visit to home terrain where she realizes how little at home she often feels there.

“Having lived in America for almost three decades, and even after a decade, you become a different person,” she said. “So you are part American and part African, and you never know how different you are until you go back home. OK. So you go back home, you are this so-called African poet who is making a lot of noise, writing a lot of crap about being African. And you go home and you realize you are more American than you thought.”

The difference manifests in everything from her subtle changing accent to the way she greets people or receives guests. With a laugh, she acknowledges that she now asks visitors to phone before they drop by – a distinctly non-African request.

Jabbeh Wesley first came to the U.S. in the 1980s, as a graduate student at Indiana University. It was to the Midwest she returned because of the civil war, living for 12 years in Southern Michigan. Now that she’s been in Pennsylvania for 17 years (she first taught here at Indiana University of Pennsylvania), she jokes, “I’m forgetting some of what it means to be a Michigander!”

Yet as she writes in her new book, “There are no rewards / in the wandering feet of exile.” At 64, she dreams of retiring in Liberia, though she adds, “I will have a home in America.” She doubts it will be in Altoona.

“I still think of Michigan as my home, my other home, because they have a Dutch culture of Dutch people who came, who immigrated to the United States during the Second World War,” she said. “And some of them still have the accent today -- a European accent. And those people were my first friends, and they understood what it meant to lose home and family and country to a war. And so they attached to me in a way that was unique, that made some of them seem like family.”