Among comics fans, Jack Kirby is legendary. But as the singular artist originally responsible for much of the multibillion-dollar entity we now call the Marvel Comics Universe, he ought to be more widely known.

Pittsburgh-based comics artist Tom Scioli’s new graphic biography, “Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics” (Ten Speed Press), tells a story nearly as dramatic as any of Kirby’s own yarns about the adventures of Captain America, the Incredible Hulk, or the Black Panther. It starts in New York City’s rough-and-tumble Lower East Side, where Kirby was born Jacob Kurtzberg, in 1917. The story later encompasses multiple eras of comics history, not to mention Kirby’s harrowing combat duty as an Army private and scout during World War II.

In a career that began in the 1930s and continued into the ’80s, Kirby created or co-created those superheroes and many more, including the X-Men, Iron Man, Thor, and the Fantastic Four, as well as their super-powered nemeses. But Kirby’s role was often eclipsed by that of Marvel publisher Stan Lee, who comics historians say had a habit of claiming sole credit for collaborative creations, and who burnished his own fame with humorous cameos in dozens of Marvel movies. (Lee died in 2018, Kirby in 1994.)

Scioli is 44, and lives in Brookline. He came to Pittsburgh for college, eventually graduated from Carnegie Mellon University, and has lived here since. He’s made his name as the independent artist behind works like “Gødland,” the “American Barbarian” series, and Marvel commission “Fantastic Four: Grand Design” -- the latter an acolyte's take on the master. The Kirby book, too, was a labor of love.

“I learned everything I know from studying the work of Jack Kirby," said Scioli.

Kirby’s signature drawing style, which reached new peaks at Marvel during the ’60s, features massively proportioned characters, action that seems to explode from the page, and forays into other worlds, from outer-space to mythic lands and alternate dimensions.

“He would create characters and universes and cultures from the ground up,” said Scioli. “The cultures that he created would have, like, fashion and artifacts and technology that were unlike anything you'd ever seen. And there's like a word that people use, 'Kirbyesque,' to sort of describe the look of these things.”

Scioli tells Kirby’s story first-person, drawing on interviews and earlier writings about Kirby to channel the artist’s voice. Kirby’s formative influences were many, from the supernaturally-tinged Yiddish folk tales his Austrian-born mother told him as a child to his scraps as the member of a juvenile street gang. Kirby read the comics of his time, of course – Prince Valiant, Flash Gordon – but in "King of Comics," Scioli has him note, “I was raised by the cinema.” And in fact, Kirby got his start professionally in the New York animation studios of the famed Max Fleischer. He also devoured pulp-fiction magazines and was dazzled by the futuristic visions at the 1939 World’s Fair.

Modern superhero comics were in their infancy in the 1930s: Kirby and collaborator Joe Simon created Captain America – Kirby’s first big hit – for Marvel predecessor Timely Comics in the couple years following the debuts of Superman and Batman. Then came the war, with Kirby surviving fearful, bloody episodes that Scioli renders with tactful gore.

Scioli spends considerable time on the relationship between Kirby and Lee. Scioli said that especially from the ’70s on, Lee tended to paint himself as “a Mother Goose or something, of comics, where he would come up with these fully formed stories and then find, you know, a talented artist to illustrate them. And that's not the case at all.”

In fact, Scioli said, it was Kirby who was most likely to develop characters and storylines, with Lee often simply writing the final dialogue. Kirby's dissatisfaction with Marvel, and fall-out with Lee, sent Kirby to D.C. Comics in the 1970s, though he returned after a few years.

In any case, Kirby saw no money from, and little credit for, the film and TV adaptations of Marvel properties produced while he was alive, including the hit TV series “The Incredible Hulk,” which aired from 1977-82. All the Marvel blockbuster theatrical movies (starting with the X-Men franchise, in the late '90s) came out after he died. In 2014, Marvel and Kirby’s family amicably resolved a multi-year legal battle over control of key Marvel characters, and Kirby and Lee are now co-credited with their creation.

Kirby has also gotten more and more of his literary due, including encomiums from a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist.

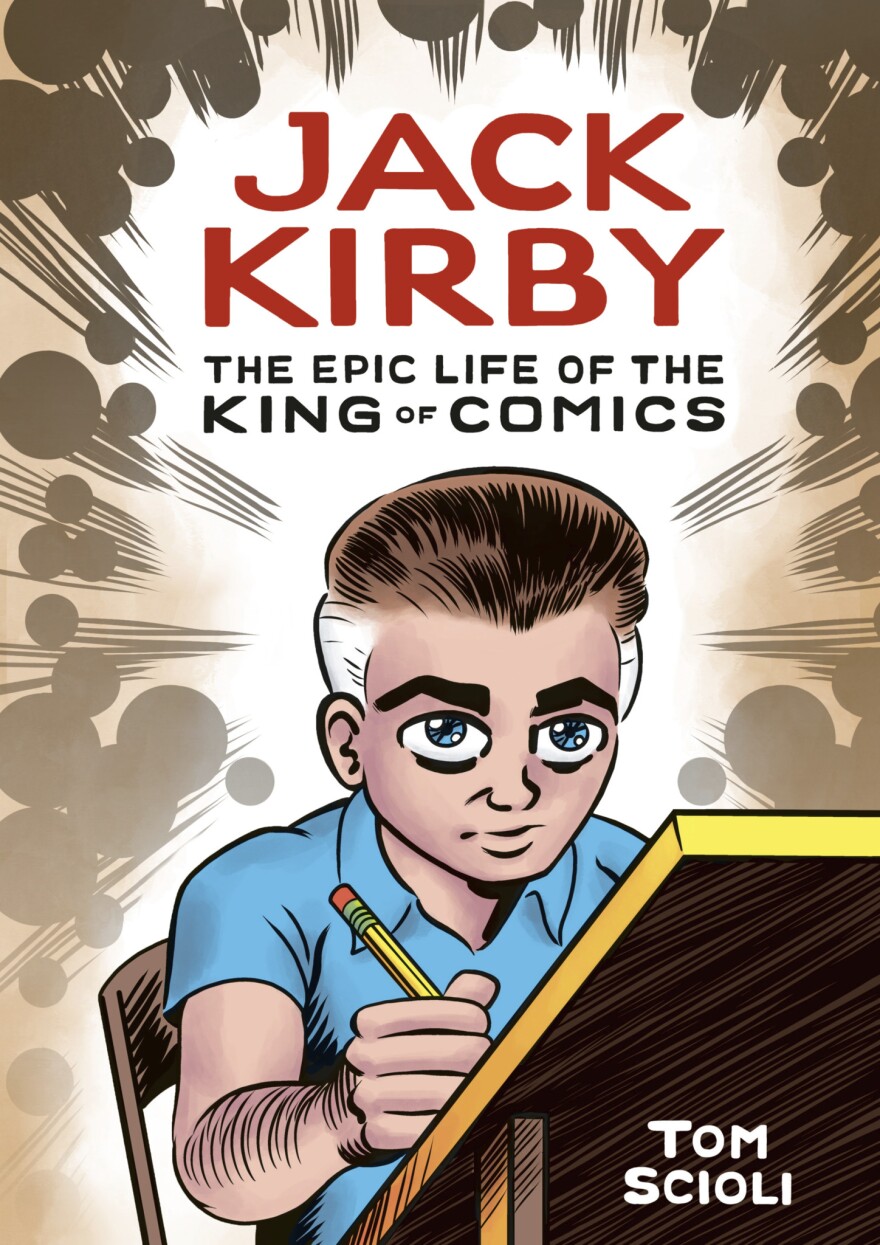

Scioli notes that Kirby did his most iconic work well after turning 40, and stayed productive for another two decades. (His world-building 1970s D.C. series “The New Gods” is another Kirby landmark.) That life-long sense of wonder is one reason, Scioli said, that in “Jack Kirby” he depicted his protagonist with the large head and extra-wide eyes of a child, even as other adults are rendered more conventionally.

“It feels almost like an illustration of the effects of the trauma of his life,” said Scioli. “The violence of the gangs and his wartime experiences, and almost like those large open eyes are sort of like the eyes of this observer who's taking everything in, and a childlike quality that he maintained throughout his life.

“Every child is able to sort of create the mental worlds that Jack Kirby does in his comics," Scioli said. "But for an adult to do that, and to execute it as an art or a craft, requires holding on to some of that.”