The double yellow line that runs down the middle of Thomas Boulevard in North Point Breeze separates eastbound and westbound traffic.

Note to readers: this story contains strong, racially charged language.

But on the 7200 block, that same yellow line separates Allderdice High School students from their Westinghouse Academy 6-12 counterparts; stand on the northern sidewalk and it’s Westinghouse Bulldogs all the way. But cross the yellow line and it’s Allderdice Dragons territory. The academic achievement at Allderdice is roughly double what it is at Westinghouse, but with fewer than half the number of economically disadvantaged students.

That’s not an accident.

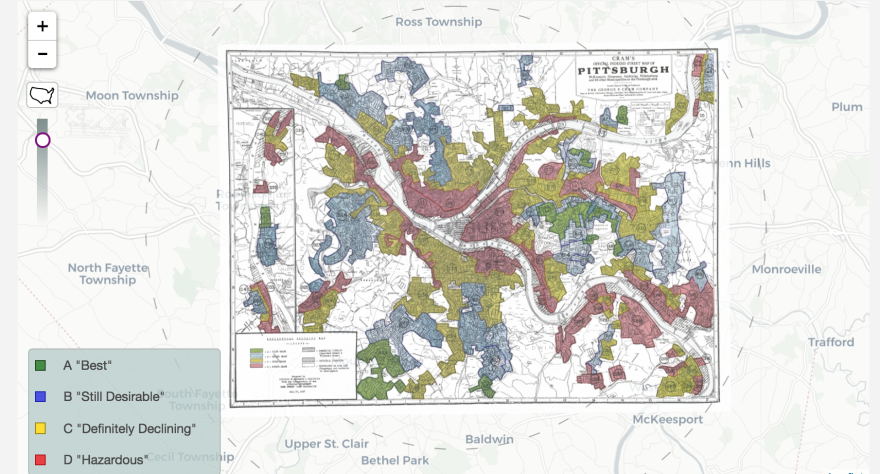

Map by Zach Goldstein*

Where families live determines which schools their children are assigned to within Pittsburgh Public. For many families, the question of where to live has often not been a free market choice.

Albert French bought his house on Thomas Boulevard in 1976. He looked for another apartment in Shadyside, but most landlords weren’t keen on his German Shepherd, Inchon.

“I decided I just would buy a damn house and be the landlord, and me and Inchon could have a place to live.”

French lived in one part of the house and rented the others as apartments. He took out an ad in the paper where he worked as a photographer, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

“It would not be uncommon for one of the first questions to be asked, ‘What side of Penn Avenue is this on?”

French is a United States Marine veteran who nearly had his head blown off in Vietnam. He did not like this question.

“They were really asking if this was on the white side or the black side,” he said. “I remember being very frustrated with it and telling them it was on the American side and hang up the damn phone.”

Policy and Prejudice

A home is the biggest investment most people will ever make, financially and emotionally, as well as the most reliable source of wealth for most Americans. For decades, that engine of social mobility was categorically denied to black families, while white families built security, said Richard Rothstein, a distinguished fellow at the Economic Policy Institute.

“They used that wealth to send their children to college, they used it subsidize their own retirements, they used it to take care of medical emergencies and temporary bouts of unemployment,” he said. “And they used it to bequeath wealth to their own children, or grandchildren, for down payments on their homes.”

Class is now a more reliable predictor of academic achievement than race. Throughout the 20th century, residential segregation created a wealth gap along largely racial lines that manifests, among other places, in performance outcomes throughout Pittsburgh Public Schools.

Rothstein’s book, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, roundly rejects the idea that segregation simply resulted from compounding and cascading individual prejudices.

“[Segregation] wasn’t the unintended effect of otherwise benign policies,” said Rothstein. “These were racially explicit policies of the federal government, and state and local as well … designed to ensure that African Americans and whites could not live near one another, that we’ve never remedied and that we all have forgotten.”

The feds built segregated public housing in the 1930s and segregated defense housing during World War II. During the postwar suburban building boom, the Federal Housing Administration refused to insure mortgages for black families in designated white neighborhoods or for white families in neighborhoods where black families lived; in other instances, the government again refused to insure mortgages in developments if homes could be resold to black families.

Chalking segregation up as de facto, a natural result of human interaction, is a dangerous myth, said Rothstein, because if it happened by accident, perhaps it can unhappen by accident. Whereas if it results from explicit government policy, “it’s a violation of civil rights,” he said. “It’s a violation of the Constitution and we have an obligation to remedy it.”

New Lender On The Block

The federal government first got into the U.S. housing market to try to pull up from the flaming tailspin of the Great Depression. In 1933 the economy was still finding rock bottom; nearly 1,000 families a day lost their homes to foreclosure. The government began to buy delinquent mortgages with treasury bonds and then resell them at low rates over long periods of time. Simultaneously, they remade the image of the typical home loan in the hopes of preventing another large-scale collapse. For a while, the U.S. government dominated the housing scene. But here’s the thing: Washington, D.C. didn’t really have any housing expertise, said Devin Rutan, who studied redlining in Pittsburgh.

“They hire all of these lenders, appraisers, real estate agents, who are … saying, it's really dangerous to lend in a majority black neighborhood,” he said. “Or having an Eastern European individual in the neighborhood makes it riskier that all of these homes are going to go downhill.”

While the maps drawn for 239 U.S. cities by the Home Owners Loan Corporation were never published, the underlying methodology was. The Underwriting Manual, issued in 1936 and 1938 by the Federal Housing Administration, helped banks and real estate agents develop their own maps. The manual warned against “inharmonious racial groups,” and the infiltration of “lower class occupancy.” The authors and their biases had an outsize, lasting effect on society when they decided who was a good bet for a loan and who wasn’t.

Rutan normalized census data for Pittsburgh so he could compare income levels and racial composition of neighborhoods over time. When compared to the map the Home Owners Loan Corporation made in 1937, striking similarities emerged, he said.

“A lot of these communities have faced 60 or 70 years of disinvestment,” he said. “The city today very much resembles a Depression-era version of itself.”

Busting Blocks

Discrimination in many forms was made illegal in the 1960s; housing discrimination was outlawed in 1968. By the 1970s the wage gap between black and white workers was the slimmest it has ever been, and more families could afford to buy homes. But private prejudice remained.

“Realtors, realizing they had all this pent-up money, decided to blockbust. I watched it,” said Ralph Proctor. A Civil Rights leader, Proctor now teaches ethnic and diversity studies at the Community College of Allegheny County.

Blockbusting is when homeowners are persuaded to sell out of fear. Realtors told white residents their property values would drop and they’d lose the most significant investment in their lives.

“You go to the neighbors and you start saying, ‘Sell me your house.’ And they say no. Why should they? They've been there forever. It's a nice home. But you need that house in order to sell it to black folk because you know you could sell it to them for more money,” said Proctor. “They always use the ghost, ‘The niggers are coming.’”

In many cases, the first sale to a black family was crucial, said Proctor. Suddenly there was proof that the thing homeowners feared was real, and had arrived.

“It's like these signs had been springloaded into their lawns,” he said. “And they went in the house and pushed the button and for-sale signs came up all over the neighborhood.”

That’s part of the reason neighborhoods like Homewood and Wilkinsburg are inhabited almost exclusively by black residents today.

Michael Eichler said blockbusting only works if black and white neighbors don’t talk about it. Eichler’s job in Pittsburgh was trying to stop the practice in Perry North, then one of the city’s integrated neighborhoods. To expose it, he’d find two couples, one black and one white, to make appointments one after another at the same real estate agency. The couples had the same income, the same savings, and the same goals.

Eichler said the white couple would be told, ‘Don’t move to Perry Hilltop, it’s a slum. Have you thought about the North Hills?’ While the black couple would be told Perry Hilltop was a beautiful community.

“And the black couple was trained to say, ‘Well, what about the North Hills?’ And the agent would say, ‘There’s nothing you can afford there.’”

Afterward, the couples would sit down with Eichler and discuss what happened. He said the experience appealed to the basic sense of fairness and decency many people have.

“I never had anybody say, ‘Well, what’s the big deal?’ It was the opposite dynamic. ‘We have to do something about this.’” he said. “They were really motivated. Not just because [of] their own experience but what they saw happen to the other family.”

The community group successfully maintained integration for a number of years, but its efforts were largely eroded by the collapse of the regional economy in the 1980s.

The ripples of those years can still be glimpsed in two high schools today. North Hills High School sits just across the Pittsburgh Public Schools border from Perry High School. More than 80 percent of Perry High students are economically disadvantaged, compared to a quarter of North Hills students; the latter outperforms in graduation rates, as well.

‘Strong And Getting Stronger’

Albert French said what he and his neighbors were aiming for in North Point Breeze in the 1970s was a community where anyone who had the money could buy a home and put down roots. It was always a good neighborhood, he said, even if people from the outside wanted to paint it as “iffy.”

“When you are about to spend $50,000, $100,000, the last word you want to hear is 'iffy.' That probably scared away a lot of good people with the word ‘iffy,’” he said. “But the community is strong and getting stronger.”

While Pittsburgh remains one of the most segregated cities in the U.S. French said he thinks attitudes have gotten better.

“I think the whole thing here is to improve a neighborhood, and be open to other people with respect,” he said. “That’s the answer.”

A young family lives in the house next door. They have four little kids and the youngest likes to chat with French when they’re both outside. At least once a month, French gets a letter asking if he’d like to sell his home.

He said he’s not going anywhere.

Check out the elementary and middle school feeder pattern maps here.

In the third part of our "Dividing Lines" series, Liz Reid looks at the district’s 30-year effort to desegregate schools. Find more at wesa.fm/dividinglines.

*This map was created using data obtained from the U.S. Department of Education and may have slight differences from the current PPS school assignments. The district’s online form is still the definitive way to determine which school a particular address is assigned to.