It’s one thing to learn economics or world history off a lecture on Zoom. But try it with dance, acting – or tuba.

Ethan Marmolejos got a sudden and unexpected taste of the latter experience starting in mid-March. While on spring break, the Carnegie Mellon University sophomore learned that campus was shutting down due to the coronavirus pandemic. He packed up and headed back to Watchung, N.J., and the house where he grew up.

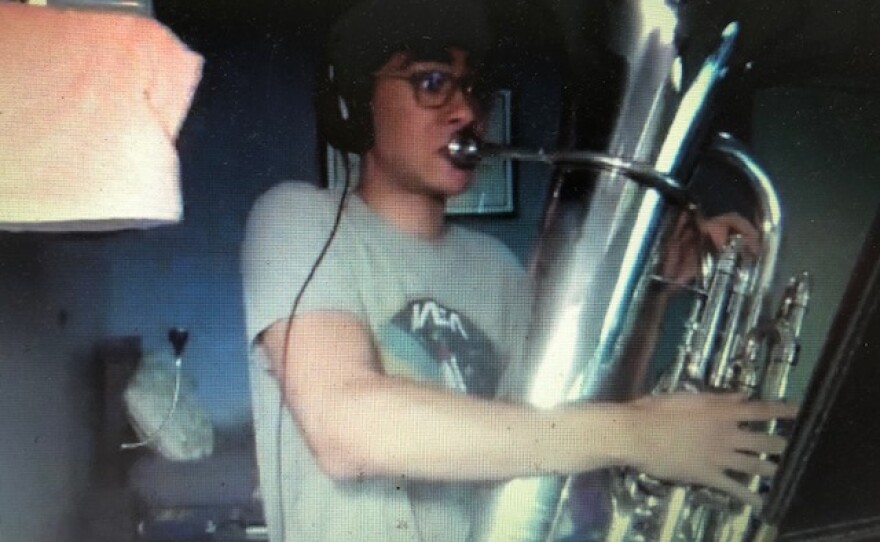

Then Marmolejos, a performance major in tuba, resumed his lessons with instructor Craig Knox, principal tuba for Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Only now, instead of sitting side by side, they were 350 miles apart, each peering into his end of a Zoom connection.

Marmolejos resumed his tuba lessons 350 miles away from campus, via Zoom

Some version of the scene was repeated across the U.S., as tens of thousands of performing-arts students sought to complete their studies this school year. Pittsburgh is a particular hotbed of such activity, with its major universities boasting nationally known performance programs.

The experience wasn’t all that bad, but it did have its challenges.

Marmolejos was one of four tuba majors at CMU, and the group had bonded. “After lessons, the four tuba players would come in and do a studio class where we’d all play something for each other,” he said. “I never had that before college.”

But online connections, useful as they are, are not yet of high enough quality to allow real-time playing or practice with other musicians -- and Marmolejos said he really missed playing informally with CMU’s three other tuba majors. The big problem is the variable split-second time delay on Zoom and other virtual platforms, which makes conversation simply annoying, but renders keeping in time with another player impossible.

Lessons, of course, couldn’t wait. But Knox said that even advanced Zoom settings can improve the audio quality only so much. Not to mention the inevitable glitches. “These things do really cut into our ability to explore that really highly refined level of color and timbre of the sound,” he said.

"Being really, really still ... is not good for live performance"

Instead, working from the basement of his home, in Mount Lebanon, Knox shifted to “learning new repertoire, working on memorization, developing sort of general strategies for effective unaccompanied performance, because everyone’s having to play just really by themselves,” he said. “It’s an opportunity to focus on, what can a musician do to work through that and still make their musical idea and the musical phrasing that much more clear and understandable to someone listening on another end.”

Acting teachers and students faced similar obstacles, said Robin Walsh, an actor and longtime theater professor at Point Park University. In March, her undergraduate students returned home to as far away as California. Many faced logistical challenges to online learning. Some shared computers with family members who needed them for work or school; one even had new responsibilities as a bread-winner, picking up shifts at Giant Eagle to help out with family members laid off.

Others were simply short on space. “One kid told me it’s like, in order for me to do any of my acting work, the only place I can get any privacy is to go out in a van,” she said.

"One kid told me it's like, in order for me to do any of my acting work, the only place I can get any privacy is to go out in a van"

Acting is about give and take with another performer in the same physical space, and her students typically do lots of partner work.

But being stuck in front of a computer screen “means you’ll be really, really still, which is not good for live performance. You gotta be moving, you gotta be grounded, you gotta have that energy moving.”

Walsh, too, shifted the emphasis of her acting class of about a dozen students. “It’s more, ‘Let’s focus on what’s going on in you, being aware of your impulses, being aware of how to do what we call ‘dropping in’ – putting yourself in the circumstances more.’”

She developed new exercises, like one for her sophomore voice and speech that focused on Shakespeare. Students were assigned to go on YouTube and critique a famous speech as performed by a professional actor. “I’d give them a whole list of things we’re looking at, like breath, and use of tempo, and use of vocal range, and do you believe them, and do they pull you in and can you understand them?”

Walsh liked how it turned out.

"Preparing finished recording products is another really good learning tool right now"

“Actually, I think I’ll keep that exercise when we go back to meeting in person. Because they made huge strides, you know?” she said, laughing. She added that some students even benefited in some ways from working in isolation, because “they weren’t worried about what the rest of the class thought, or what the rest of the class was doing, and it wasn’t a one-size-fits-all kind of warm-up.”

There was also a benefit on getting students to work with audio and video recording technology. “People self-tape on their phones for their auditions all the time now. It’s huge. It’s a big win” to get students to do it, she said.

Knox said he also pushed his students on the multimedia production front.

“Preparing finished recording products is another really good learning tool right now. … I’m giving them an assignment of a piece I’d like them to work on and created a finished product as a video recording, or it could be an audio recording.”

The finished product provides a way to evaluate a student’s performance in a way impossible with a shaky online connection. It’s also the way music students would be doing their final projects this year, rather than live in front of a jury.

“Also, I’ve been thinking a lot about how important sharing recorded performances is becoming on social media, especially right now when there’s no other outlet for people to share or receive performances,” said Knox, citing the PSO’s own online programming during the pandemic.

Marmolejos said he’s enjoyed learning such skills. “One of our projects is we have to make an overdub. You record yourself a bunch of times and then you lay them over. So you kind of play with yourself, in a way. Like with an ensemble of yourself. … I did not know how to do that before.” (The piece he was preparing for his final project was John Williams' Concerto for Tuba.)

Knox emphasized, though, that for a performer, there’s no substitute for live experience.

“It’s one thing to perfect something in the practice room, but it’s another thing altogether to be able to stand in front of people and in a live performance situation and play your best,” he said.

No one knows when that will be possible again – or, indeed, when students and teachers exploring any subject will again meet in a physical classroom.

Walsh hopes it’s soon, but found a silver lining in the brave new world of teaching remotely during the shutdown. “I think in a weird way it brought people together,” she said, laughing. “And there were really good things that came out of it that I hope we hang on to.”