At first glance, the finances of the Pittsburgh Public Schools look healthy. It has nearly $112 million in the bank, and the district hasn’t closed a school since 2012 or raised taxes in five years. But early budget discussions, and a dispute with Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto may be a sign of trouble to come.

District Chief Financial Officer Ron Joseph says expenses -- like payments to charter schools and retirement costs -- are growing faster than revenue. The proposed 2020 budget must address a $27 million deficit, and Joseph said if something doesn’t change drastically, the district won’t be able to cover expenses by 2022.

Pittsburgh Public School officials presented four options – including a property tax hike -- to the school board earlier this month.

“We will want to go to Harrisburg first and ask those questions about the viability of us getting those funds back. We’ve been told to have a conversation with the city, which we will begin to do,” said Superintendent Anthony Hamlet.

Both the City of Pittsburgh and the Pittsburgh Public Schools district charge an earned income tax on city residents. But 15 years ago, when the city was on the verge of financial collapse, state legislators took some of the school district’s revenue and began diverting it to the city.

Now that the city’s finances are healthier, district leaders say they may seek to end that diversion. Doing so would give the district an extra $20 million, or somewhat less than 3 percent of the annual budget.

That idea didn’t please Mayor Bill Peduto. When asked about it after his own budget presentation this month, Peduto said the city had to undergo state financial oversight in order to receive the diverted revenue. If the district wants the money back, he said, it should go through a similar process.

“There are several questions over how the schools have been spending money these past several years, and there hasn’t been much oversight,” he said.

Under state law, school districts must be in a state of financial distress to be placed under state oversight. PPS isn’t on the state’s watch list for troubled districts.

Peduto’s remarks drew criticism from advocates like Angel Gober, who said he should “stay in his lane.”

Gober is the Western Pennsylvania organizing director for the activist group One PA. She said she wasn’t surprised by Peduto’s remarks. The mayor has at times been critical of district leaders, and “he hasn’t gone out of his way to build … a working relationship and how we can improve our schools.”

James Fogarty, the executive director of the advocacy group A+ Schools, said he understood the mayor’s frustration, but his hope is that the city and district can learn to work together and, “find a way that kids can win.”

Weighing Options

City Controller Michael Lamb’s office monitors district finances. He said the schools were in a less dire situation than the city once was: “We were in far worse condition than the school district is.” But he said the district also suffered from problems of credibility and a lack of openness.

That includes Hamlet, the superintendent, who has been caught up in controversies -- including trips taken to Cuba and a failure to correctly complete ethics statements. In any case, Lamb said the schools can't put off dealing with their financial problems forever.

“You look at a district that continues to lose enrollment and continues to have a lot of buildings. They’ve got to make some hard decisions,” he said.

No administrator has proposed closing schools, but enrollment is down 17 percent in the last decade. Only about 58 percent of the district’s total capacity is currently being used.

Joseph, the district’s Chief Financial Officer, told the board that officials are trying to make better use of the buildings they have. They’re starting a process they call “re-imaging the district” to get community feedback on the patterns that determine where kids go to school.

“We know we have some schools that are under-utilized and some that are bursting at the seams in terms of their enrollment versus their building capacity,” he said during a budget workshop. “So that’s something that we intend to look at.”

Hamlet says every budget solution is on the table. When asked by WESA’s The Confluence last week if schools should be closed, he said, “I would say anything is possible,” he said. “But one of the things you want to make sure that whatever happens moving forward that we will increase our opportunities for our students, our educational programming will get better as a result.”

Hamlet said he’s not looking to reduce staff, but he has asked Joseph to reduce central office budgets by 10 percent.

Outgoing Board President Lynda Wrenn said she prefers that cuts take place outside of the classroom, and potentially in administrative offices. But she said there are hard decisions ahead.

“I want to see kids have programs that have, you know, music and arts and after school activities,” she said. “I mean, I want all that. I want health service. I want great teachers. But unfortunately, we can't have everything we want.”

The other eight current school board members either declined or didn’t respond to a request for comment this week.

When the board convenes next month it will have three new members who campaigned against further school closings. During her campaign, for example, incoming board member Pam Harbin said that closing a school is a form of “violence.”

Gober, with activist group One PA, said closing a school is not an option.

“Communities need their schools just like communities need affordable housing and access to jobs,” she said. “Because here's the thing: Like even some of the schools that are low enrolled -- we've been fighting for smaller class sizes for years.”

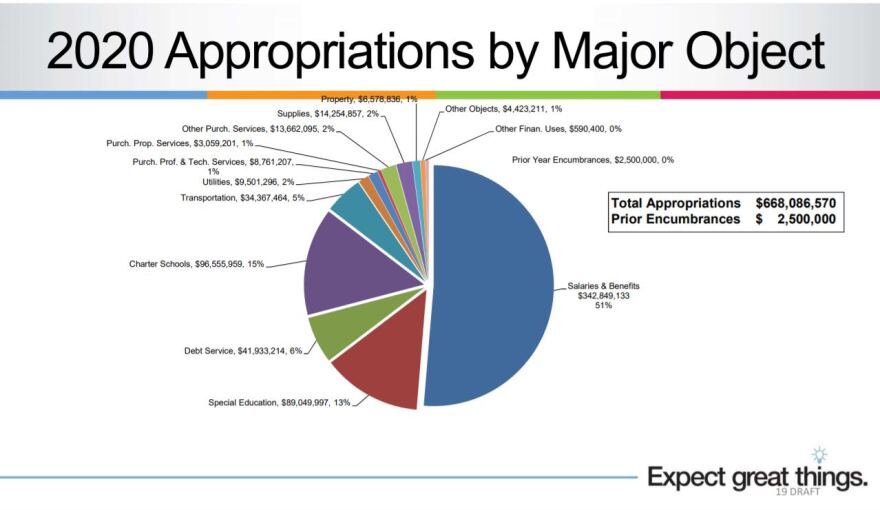

Gober said one budget solution is reforming the charter system. When a student living in Pittsburgh attends a charter school, PPS sends money to that school to cover the cost of educating the student. In all, those transfers amount to about 15 percent of the PPS budget.

Fogarty, with A+ Schools, said that if residents oppose any changes to how school buildings are used, the district will have to make hard decisions about programming.

“Then this district has to show people the books and say, ‘Look, here's the consequence of that. Like, it means we can't provide music education starting at third grade unless we add this much in taxes,” he said.

Property Tax Increase

Even if the board approves a property tax hike at its December meeting, Joseph said the district will have work to do in 2020.

The increase would amount to about $4 million, less than 1 percent of the district’s annual budget.

“It’s on us to really look in 2020 and make some decisions about our programming, to see if we can make any headway in any discussions about increased revenue, to see if we can have some success on the front of trying to get some charter reform,” Joseph said.

Members of the public can weigh in on the board’s budget during the next public hearing Dec. 2 at the administrative office in Oakland.

WESA’s Ariel Worthy contributed to this report.