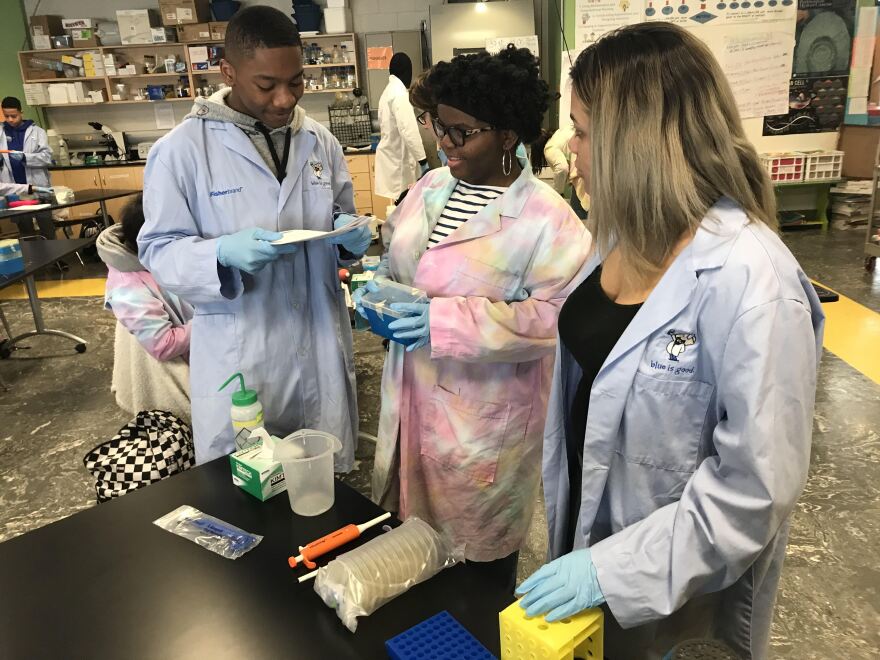

Sixteen-year-old Isabelle Walker sits at a black lab table wearing a lab coat. She stares down at a petri dish.

“We’re trying to see how different bacterial colonies grow in different conditions,” she said.

Walker and her classmates at Pittsburgh Public’s Science and Technology Academy in Oakland know that the experiment they’re conducting will show that bacteria adapt.

But early on, that’s about all they know.

According to their teacher, Edwina Kinchington, that’s part of the process.

“We want you to learn it as you go along,” she tells her 10th grade microbiology class. “Why are we doing this? Because bacteria are everywhere. Some are good, some are bad. Some cause disease, some don’t.”

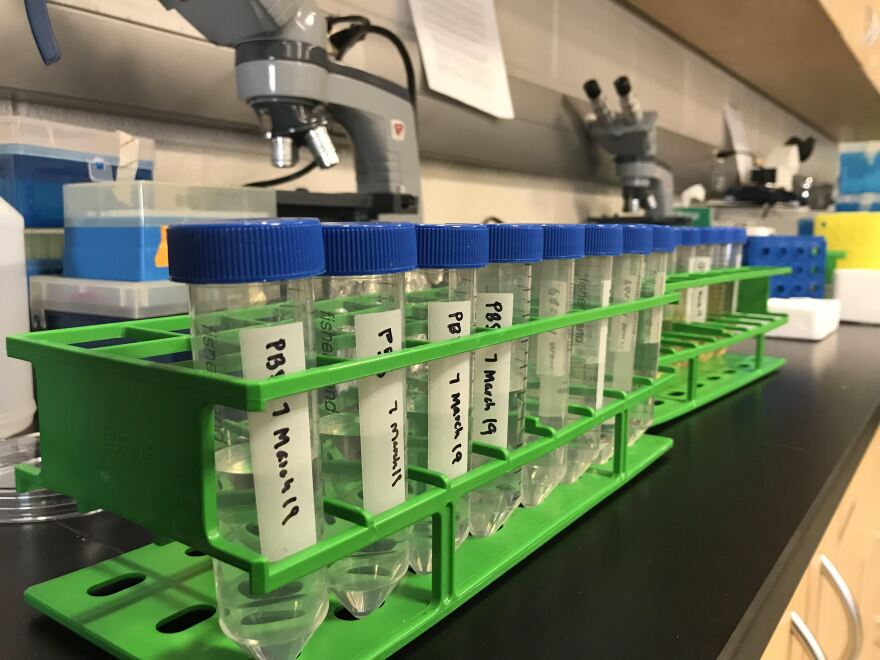

The students add a common strain of bacteria to a test tube along with a plastic bead. Over a few days, they transfer the bead to a new test tube. Only the bacteria that attach to the bead transfer to the tube.

The students work in groups and follow written instructions. They make a few mistakes along the way.

Jay Brown, 15, is in Walker’s group. The research question they develop together asks if there will be a difference between biofilm production in the irregular colonies and the control colonies.

The bacteria that attach to the beads have done so by producing biofilm. The mutants multiply rapidly and produce new colonies that look different because of their increased biofilm production.

Biofilms are the cause of a large number of bacterial infections and are often more resistant to antibiotics.

Kinchington explains that to the students. But she never explicitly states the larger concept she wants them to grasp.

The students are learning about – and watching – evolution.

Hands-on learning

Kinchington collected assessment surveys from students before she began the module. She said a common misconception among the students was that evolution takes a very long time. In this experiment, students saw change in one week.

“So they can actually see that the bacteria are adapting and growing on the bead because those are the ones that like to adhere,” she said. “That’s what we’re selecting for.”

Pennsylvania’s public education standards state that by the 10th grade students should be able to explain how evolution through natural selection can result in changes in biodiversity. They’re evaluated on that understanding through standardized tests.

But, the state’s department of education doesn’t tell schools how to instruct their students. Lessons are left up to teachers. That could mean that schools rely on textbooks and images of Galapagos finches that Charles Darwin noted had beaks that varied in form and function. The birds played an important part in Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Scientist Vaughn Cooper argues that too many classrooms rely on passive historical lessons. That’s why he created the hands-on curriculum that Kinchington began using this year.

“The first time I saw as a graduate student bacteria evolving in real time and you could see the differences, I knew that this had to be the way that we learn about evolution,” he said.

Cooper’s program, EvolvingSTEM, is being used in about a dozen schools in three states including local school districts like Peters Township, Seneca Valley, Sewickley Academy, Winchester-Thurston and two Pittsburgh Public schools.

There isn’t a fee associated with the curriculum, and Cooper tries to help classroom teachers who use the materials.

“His goal in my, opinion, is he wants to teach the next generation about evolution in an inquiry-based, hands-on way. To help students understand what evolution is whether it’s to get a few more points on the Keystone [standardized exam], or you know just to have the concepts correctly integrated,” Kinchington said.

By the end of the module students are supposed to be able to see how their bacterium that began in a benign state ended as a diverse and adapted population.

Cooper is a evolutionary biologist and director of the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Evolutionary Biology and Medicine. He also runs a lab in Pittsburgh focused on understanding how bacteria adapt to new environments and form communities within biofilms. In a visit to the Sci Tech classroom, he told the students that his lab is studying biofilms because they create drug resistance in people with diseases like diabetes.

Kinchington’s class also discussed how biofilms can affect people with Cystic Fibrosis. That issue is at the forefront of a new movie “Five Feet Apart” about two teenagers with the disease who spend a lot of time in the same hospital. One of the teens has a resistant bacterial infection, so they must stay five feet apart from each other.

“We talked about the meaning of that and why it’s important and related to the research we’re doing in class,” Kinchington said.

Mixed results

Cooper’s curriculum requires students to ask a lot of questions, which Kinchington said is useful.

“The most fun honestly is to watch them make mistakes and learn from them,” she said. “I they like me to tell them the answer and they don't like that I don't tell them the answer. The other is putting the data together in the final poster as a group. They start using good scientific vocabulary and they start making meaning out of what they’ve been doing and that is very satisfying.”

The lesson was frustrating for Walker. She says she didn’t see evolution in action.

“We didn’t really see that happen because we took the bead at the very end and we scanned it to see what biofilms were formed but we didn’t see what started out and how it ended,” Walker said.

Now, Kinchington’s class will use what they’ve learned from the module to focus on the human microbiome and will learn how to identify different types of bacteria. Then students will create their own research project.

“Some have been looking at the bacteria that accumulates on retainers, computers and bathrooms and doorknobs, those kinds of things,” she said.

Kinchington said these types of experiments require a lot of prep time for teachers, but the payoff is engaged students.

“It is hard. But I would implore all teachers to give it a try because the engagement of the student is so much stronger than any type of lecture,” she said.