Traveling from Forbes Avenue on Duquesne University’s campus to the South 10th Street Bridge, drivers and pedestrians making a right into the Armstrong Tunnel encounter something unusual for a tunnel: a curve.

The 45-degree bend occurs near the northern portal of the tunnel, which runs a quarter mile. Good Question listener Eric Shaffer grew up in Pittsburgh’s South Hills and went with his father to work in the Hill District on the weekends. Driving through the tunnel as a child, he always wondered about the curve.

“I asked my father about it and he said there were a lot of different stories,” Shaffer said. “One was that the engineers made a mistake, but that didn’t seem quite right.”

For a school project, Schaffer looked into the tunnel’s history, but was never able to find a definitive answer about the bend. Some speculate the design was a planning mistake, but Mike Burdelsky, assistant manager of bridge engineering for Allegheny County, said that’s not the case, the curve was intentional.

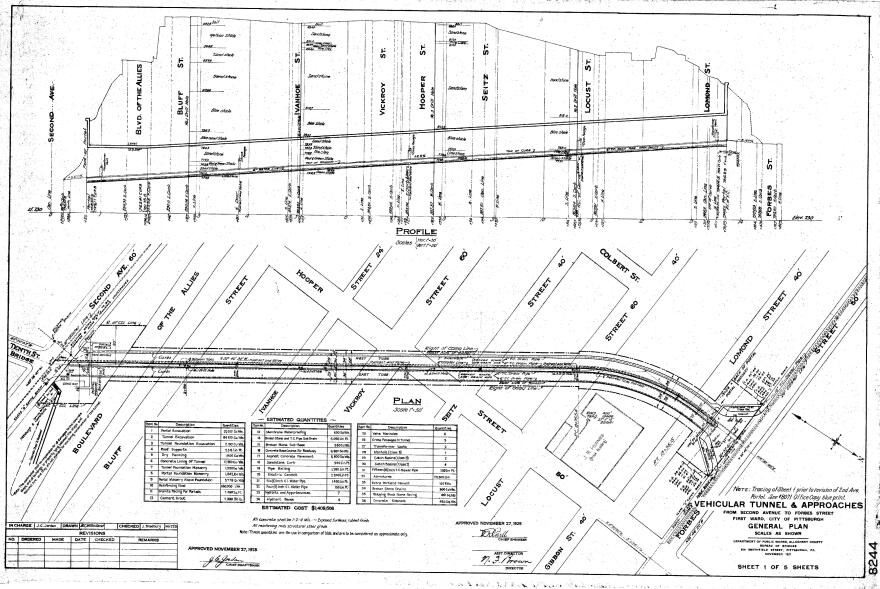

“It was included in the original design drawings that we have on record,” he said. “It seems to be for traffic purposes, to line up with the 10th Street Bridge on the Second Avenue side. And then on the north portal at Forbes Avenue, it comes to a t-intersection.”

He said the tunnel was designed to line up at a 90-degree angle with the streets on both sides, which makes it easier for traffic to cross through the intersection and turn. The streets run parallel, but are positioned diagonally, so in order to make a t-intersection at Forbes Ave., the tunnel must have a curve.

This is part of our Good Question! series where we investigate what you've always wondered about Pittsburgh, its people and its culture.

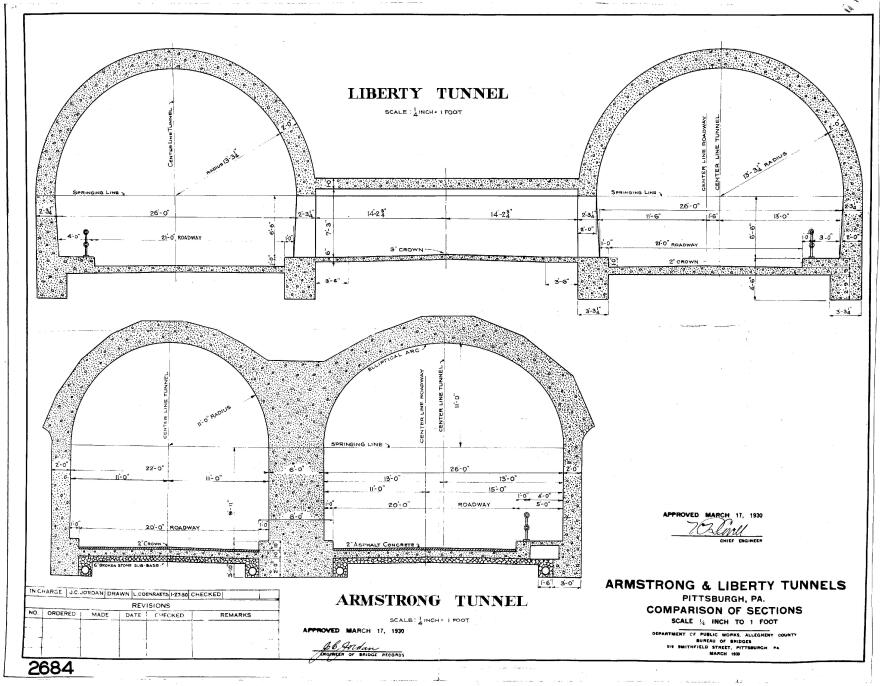

The portals of the tunnel were made by StanelyRouch, the same architect who designed the Smithfield Street Bridge, and the Armstrong's design is similar to the Liberty Tunnels, but on a smaller scale. The off-white ceramic tiling inside was added to help with illumination during a refurbishing in the 1990s. It's slated for another restoration in 2020, meaning the nearly 12,000 drivers that use it each day will have to find a different route.

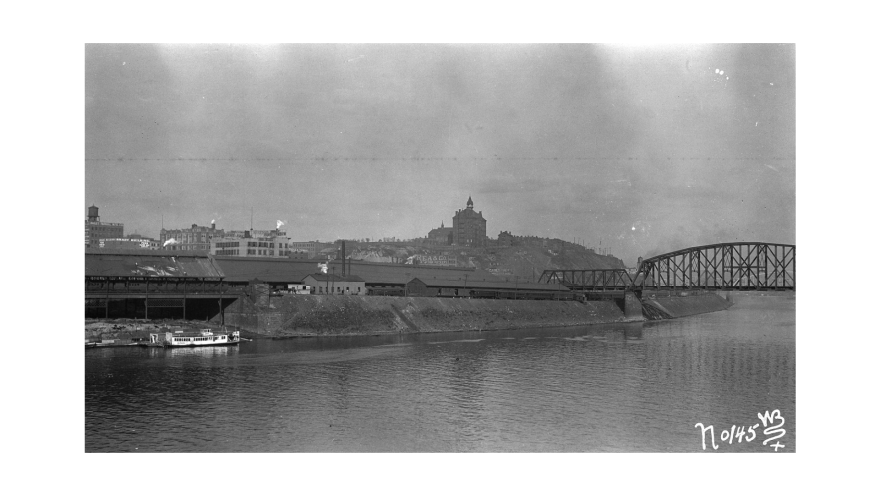

The area around the Second Avenue end of the tunnel and the land on top of it has gone through a lot of changes, too. The Bluff, home to Duquesne University’s campus, was once a bustling upper-middle class neighborhood, according to archivist Thomas White.

“Directly above the tunnel was houses, mainly, but there were also warehouses and brickyards here on the Bluff,” White said. “The Bluff, in general, was full of lots of different businesses.”

The Bluff covers about one-third of a square mile, or a little over 200 acres. It used to be called Ayre’s Hill after an engineer who wanted to build Fort Pitt there instead of The Point. But later it was renamed Boyd’s Hill after a newspaper businessman, John Boyd, who killed himself on the land.

In addition to brickyards, White said there was also a garage that housed the trucks of Reick’s Dairy Farm, an orphanage and a small hospital.

“Many of these were later converted into academic buildings,” White explained. “The neighborhood was really a mix of people living close to the city who were maybe middle class, but there were also, as all of Pittsburgh was, the industry and the business was just mixed right in.”

White said currently weight from land and property above the tunnel isn't a concern, but when Duquesne builds new facilities, they have to consider how construction might impact the land.

“There’s a lot of space between the ceiling of the tunnel and the bottoms of these buildings, but it has to do with the weight and the layout and what kind of vibrations can be done,” he said. “You couldn't put a small college stadium on top.”

On the southern end where the tunnel meets the bridge, there used to be a large industrial area with a few houses. White said among multiple railroad tracks, the Pittsburgh Gas Works and a brewery operated where the Allegheny County Jail is today. There was also the Fort Pitt incline, which ran from Second Avenue to Bluff Street. The path is now marked partially by public steps leading to Duquesne’s campus.

The tunnel was named after Joseph Armstrong, former County Director of Public Works, Commissioner and Mayor of Pittsburgh.