Photos and paintings at The Andy Warhol Museum are set up chronologically by decade, starting at the top.

From the seventh floor, School Programs Coordinator Leah Morelli explains, “This is the floor in which his early life starts and the story begins.”

But even without a human guide, all visitors -- including those with visual impairments -- will soon have a tool to let them know where they are and what’s around them in the space thanks to the organization’s first audio guide.

“Usually on an audio guide, when you go to a museum, you see a number on the wall and you have to type that number in and press enter to hear the content,” Digital Engagement Manager Desi Gonzalez said.

Rather than manual entry, the Warhol is using technology called bluetooth beacons to push out content based on where visitors are located.

Cultural institutions from around the world get a sneak peek of that technology this week as part of the Leadership Exchange in Arts and Disability conference, or LEAD, which is being held locally at the Westin Convention Center in Pittsburgh for the first time.

The museum will share some of its best practices and accessibility initiatives with attendees, including the audio guide.

The guide application breaks down each location’s content into chapters and starts with an introduction.

In the gallery, Gonzalez hits play on her app, and a deep voice streams from her phone.

“Hi, my name is Donald Warhola. I’m a nephew of Andy Warhol, and I work here at the Andy Warhol Museum. Andy Warhol was born Andrew Warhola in the Soho section of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on August 6, 1928, and he lived here until he graduated from Carnegie Tech when he was 20 years old.”

But what comes next isn’t your typical audio tour. Gonzalez said the Warhol developed its first guide with accessibility in mind from the start. It includes selectable content for those with visual impairments like descriptions of the work.

The next chapter goes on: “6-foot-tall, 4-and-a-third-foot-wide canvas, features a single can of Campbell’s soup with a ripped and pealing label. The large black and gray can stands just to our right of center, rendered in graphite and thin casing paint.”

The application was all developed in-house by the innovation studio at the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh.

Chris Maury, 29, who provided feedback throughout its design process, said he’s looking forward to the app's official launch.

He’s the founder of a Lawrenceville-based startup company in Pittsburgh, Convesant Labs, that designs tech for people with visual impairments. Five years ago he discovered he was slowly losing his own vision.

“[The optometrist] couldn’t fit a new prescription; my eyes just wouldn’t adjust correctly, and he was like, ‘That’s weird,’” Maury said. “So he took photos of the back of my eyes and saw scarring in the center, which is indicative of this retinal disorder called stargardt macular degeneration, which is what I have.”

Maury said he won’t be legally blind for a few years, but as-is, he can no longer drive a car or read restaurant menus. Overall, he said he’s still able to do 90 percent of what he could do before.

After his diagnosis, Maury founded Pittsburgh’s accessibility meetup, a group that focuses on technology and advocacy. The group works with the city to prioritize accessibility infrastructure and provided feedback throughout the Warhol’s audio guide development.

Maury said the goal of any application should be universal design so every user can have a positive experience.

“Throughout this entire process, from kind of the brainstorming phase to actually building it and testing it with users, it’s, ‘What are the needs of people with disabilities? What are the features we need to support? What are the needs of everyone else?’" Maury said. “How do we provide the best experience for both of them in the same space?”

Warhol staff said consultants, researchers and community members found that between the disability community and broader community, many needs were the same.

Danielle Linzer, the Warhol's curator of education and interpretation, said making a welcoming and accessible space is about anticipating diversity while creating physical spaces, programming and products.

One size never fits all, she said.

“We’ve really been thinking a lot about choice,” said Linzer. “How can you provide individuals with disabilities with the same kinds of choice, the same kinds of opportunities that general visitors can come to expect from cultural institutions?”

Linzer said the museum will continue developing initiatives like sensory-friendly programming. The organization also uses portraiture to help people on the autism spectrum understand facial expressions and non-vocal communication.

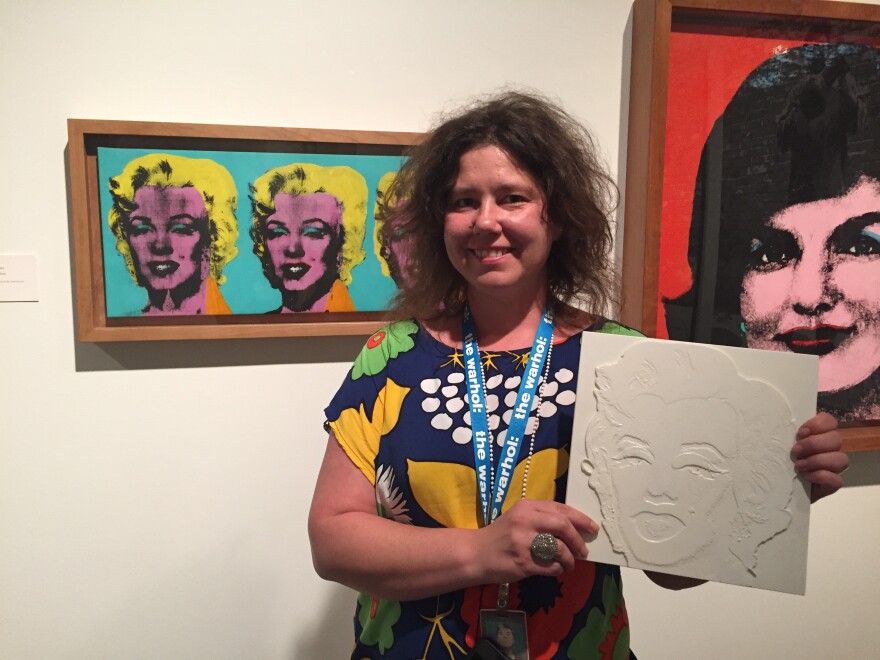

During the LEAD conference, the Warhol is premiering several tactile reproductions of paintings to help visitors with visual impairments understand the shape and contour of works on display.

“Access is something that’s never really done,” Linzer said. “It’s not like, ‘Oh, we checked that box. We finished that work.’ It’s really about an almost philosophical approach and a practice of engagement, and it’s something that we are continually working to improve here.”